Alien Landscape at Nigoj Kund

It all started with a post made by my friend Gyaneshwar on the IIMC@Pune WA group. Nigoj Kund, about 72 km from Pune, seemed ideal for a weekend ride. We were not too sure about whether we would find a place to stay overnight – but that got resolved when one of the missus’ doctor friends introduced us to Yogita Lalje, who had worked as a nurse at his hospital. Her in-laws stayed at Nigoj – and we were invited to stay over at their place.

Giri, yours truly and the missus started off on Saturday morning. The missus was in a birthday mood – and to make life less strenuous – and to keep up with the boys – she was using her Pedaleze Electric cycle. Winter, the best time for rides in Pune, allows you the luxury of a late start. We left home at 0715 – and because of a miscommunication in the meeting place ended up spending 15 min at Yerwada metro station waiting for Giri, who stays at Sopan baug.

Caught up with an electric rickshaw owner to check with him about his feelings about his new vahan. His 2 month old TVS rickshaw’’s actual cost is Rs. 3.5 lakh, but financing the 10.5 K EMIs for 4 years makes it closer to a 5 lakh outflow. The range is 180 km – and he has tested it by doing a round trip to Jalgaon on the rickshaw. He has set himself a target of earning Rs. 2000 per day – and starts at 0600 hrs everyday to meet the target. The end of the day is whenever the target is achieved (usually 1900 hrs. There is a break in the afternoon, which is used for charging the driver and the gaadi.)

He owns a tapri close to the metro station – and that is the venue of charging. He saves Rs. 500 per day when compared to CNG! Our friend cut out a Rapido offer to continue our conversation. At Rs. 45, the fare is not going to help meet his targets. The minimum fare has to be Rs. 100 for him to accept a ride. Just then, I got a call from Chief (as Giri is fondly called in our group). He was waiting for us at Kharadi – 6 km down the road. End of conversation.

Met with Giri and continued our highway ride. We took a bio-break at a Food Mall at Koregaon Bhima. One advantage of using the loo of a food mall is that there is no obligation to buy junk food or any kind of food. We used this opportunity to do some fruit snacking. We had carried fruits along – as it is difficult to find fruit stalls open early in the morning. Fruits are the best food – especially in cycling. Fructose is a carb that doesn’t make you drowsy and is good fuel to keep you on the saddle for an hour.

Plastic Mesh Tree Guard with stick support

A proper breakfast – or you could call it brunch was at Shikrapur, where we said bye bye to the 6 lane national highway. We had now covered 40 km of the 72 km ride. The highway hotel had a 4 item menu card: misal, wada pav, milk-sugar tea and without sugar coffee. We had the misal and the tea / coffee. The Missus’ cycle breakfasted along with her – as we could manage a plug point next to the table.

Shikrapur is connected to Malthan by a two lane road – that is still one lane in patches where road width is being expanded. There was a small stretch of unpaved road near a newly constructed bridge. Save for a lone factory, Mutual Automotive, which makes bumpers and large plastic parts, the road was dotted with only a few houses and shops. The tarmac quality was not up to NHAI standards – but for a cyclist the real pleasure is in hearing bird songs, seeing green fields and enjoying the shade of a sparse tree cover. Winter cycling is done with layers of clothes, with the outermost layer always being the most colorful, as you want lorry and car drivers to be aware of your existence. It was 1100 hrs – and the winter sun started warming up enough for yours truly to de-layer.

Road near Malthan

Malthan is barren rolling terrain, and so has a lot of quarries. I am sure that there were forests here once upon a time, which were converted to fire wood long ago. We came across a few dumpers – surprisingly all empty. Malthan is also connected to Ranjangaon industrial area, and I guess most dumpers’ loads are meant for construction sites there. Apart from dumpers, the other traffic was sugar cane laden tractor trollies. There is a sugar mill 4-5 km ahead of Malthan. One thing that is common to tractor drivers across the country is their love for music. Given the noisy tractors, the music is even noisier. For a km ahead, the road becomes DJ land and one can listen in to the latest hits of the local area. Our DJ seemed to be from the north – as he belted out mostly Hindi fare.

Deweeding Water Channels

We stopped for a tea break at Malthan – it was around 1230 hrs by then – and the destination was just 15 km away. 1 km down the road, one takes a right turn at Jayesh hotel (probably closed down). I got chatting with a local who was motorcycling to a nearby farm. Barter is the way of life in villages. Our motorcyclist friend was a pujari and was on his way to collect onion from a farmer bhakt. A few weeks later the farmer would get kirtans in exchange for the onions.

Spray Irrigation in Onion Field

From Malthan onwards, one could glimpse an onion dominated agrarian economy. We value staple crops like rice and wheat as they store well. Onion is a semi-staple in some sense. Unlike rice and wheat where the government’s minimum support price helps keep prices stable, onion sees higher standard deviations in pricing. The onion market relies on distributed energy-efficient farm level storage to match supply to demand through the year.

A typical onion warehouse is usually close to the road, about 5 ft wide and length which ranges from 20 to 50 feet. The length of the warehouse being an indicator of the prosperity of the farmer. The structure is typically made of steel angles or tubes with an asbestos or steel sheet sloping roof that extends 2 ft out of the walls. The walls are chicken mesh wire – lined by straw. The floor of the shed is a foot or two above the ground. This arrangement for onion bulbs storage allows for aeration, yet at the same time helps keep water out.

Every year around winter time, onion prices crash. The old must make way for the new. Farmers follow FIFO principles and do a stock clearance to empty their warehouses for the new harvest. We caught up with a team that was loading warehouse onions in net sacks. There was a pile of sprouted onions – which is typically written off. You can reuse sprouted onion bulbs to grow edible green shoots but they don’t typically grow into large, full-sized bulbs. Next time you see a sprouted onion in your kitchen you can transfer it to your balcony pots – and enjoy the kaanda paath after a few weeks.

Onion Sacking

The Jayesh hotel road ends in a T junction, where one takes a right to hit another T junction. which is where one zig zags a bit to continue to the Nigoj road. The Nigoj kund (potholes) are 4 km before Nigoj town. The Kukadi river is the boundary of Pune and A’nagar districts. (Old Ahmednagar – now Ahilyanagar).Lunch was onion bhaaji – and it was more to ensure that we had a safe place for parking our cycles and bags as we moved around.

Pomegranate Shrubs – need to be supported as the fruits are too heavy

Guava Shrubs – Fruits are covered with plastic to keep birds away

In earlier times, the area used to see much more rain. As the Kukadi River flowed out from the hills, it scoured the black basalt rock and formed the potholes and the gorge. Hard pebbles carried by the river got trapped in cracks in the basalt. The swirling water current made these pebbles rotate rapidly, grinding away the rock to form smooth, circular potholes (kunds). The formations resemble natural rock sculptures, with smooth, rounded shapes.

Check Dam

There is a check dam upstream of the kund. The erosion area starts around 100 m downstream of the dam. One can see a few trees cosying up in crevices – using the dampness of the rock to draw water. These trees also have a role to play in the erosion – bioweathering. One realises that the roots hunger more for minerals like phosphorus rather than water. And also how an eco-system develops with microbes and fungi which break down the rock minerals into tree usable form. One can walk down stairs to the gorge and admire the fish that seem to be enjoying the aerated waters. And admire other winged fish admirers – the kingfishers, herons and some smaller birds.

Road bridge to Nigoj village in the Background

I guess all rocks are not equally hard – and probably the erosion is more in areas where the rock is softer. There are multiple streams that form and converge into a single stream which has cut through the rock to form a gorge. The gorge runs a few hundred meters before the waters empty into the plains below the rocks. Must revisit Nigoj in monsoon, to see the river in flow – and catch the erosion in action.

The salt deposits on the rock indicate usual water levels

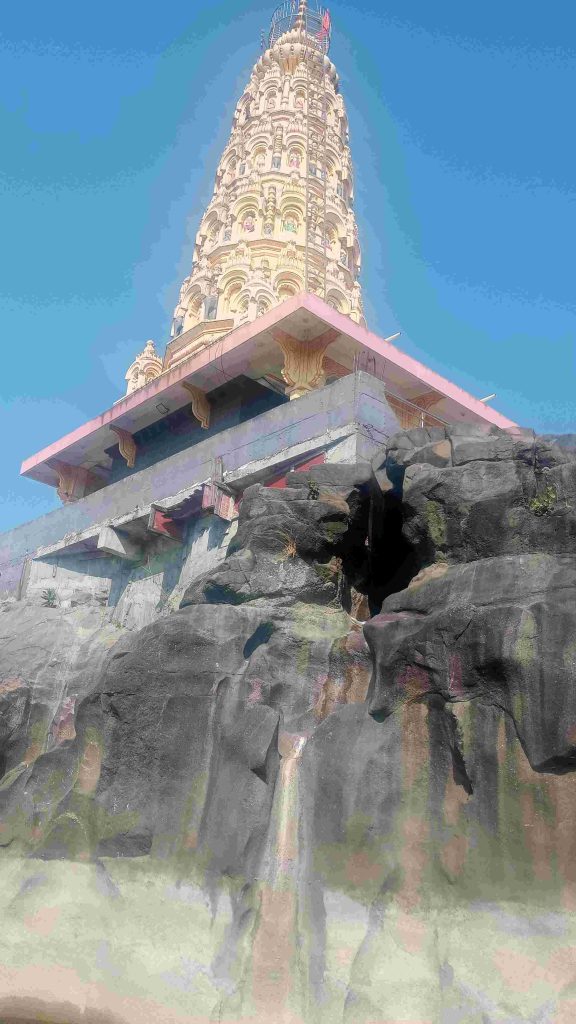

The local goddess, Malganga, has two temples on either side of the river devoted to her. (Fun fact: both are in different districts.) Navratri is when there is an annual festival – which sees a footfall of a million. The more popular gods are the ones who are supposed to grant wishes to their devotees. Malganga Devi is supposed to help get the stork home. Was worried when the missus actually purchased some coconuts and made an offering to the devi. I don’t think our daughters, who are in their twenties now, are looking out for any more siblings!

Malganga Temple

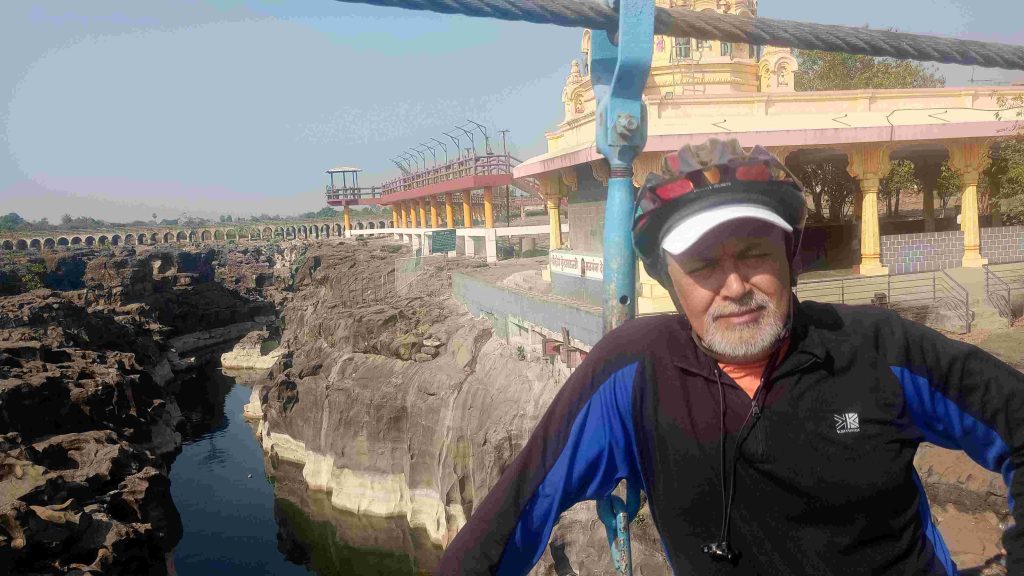

The Suspension Bridge

A hanging suspension bridge connects the two temples. A favorite pastime of younger tourists is to do some group jumps and army marches to sway the bridge. They have probably forgotten how similar stunts lead to a collapse of a suspension bridge in Morbi, Gujarat in 2022. I do hope civil engineers build sufficient factors of safety in their designs to accommodate such stunts. We then went on for a short stroll along a concrete walk-way along the river. Felt much safer admiring the erosion from an elevation without any oscillations.

Chief on the Swaying Bridge with the more stable elevated walkway in the background

We spotted a small hoarding for a lodge & decided to check it out. Turned out to be decent. We thought it would be a good idea not to stretch the hospitality of the Laljes, our Nigoj hosts, and booked two rooms at Nisargraja hotel. Yogita’s better half was visiting from Pune – and he met up with us near the Kund. We had ice-cream at a handcart on the road. The ice-cream guy had migrated from a village in Bhilwara to set up shop here. Rajasthan entrepreneurship is difficult to match. He already had expanded operations from one cart to two. The other was in Takali Haji, which we had crossed on our way to Nigoj.

Although we never met Yogita, we realised the difference that an enlightened mother makes to a family. Yogita’s husband drives a rickshaw and they stay in Slum Rehabilitation Authority flats in Charholi, near Alandi. The kids are following in the mother’s footsteps. The son is pursuing his B.Sc in nursing. The daughter is pursuing her BAMS degree at a college in Bhimashankar.

After our ice-cream snacking, we cycled down 4 km to Nigoj town. Yogita Lalje’s father-in-law was waiting for us at the town’s Malganga temple. We were instructed to do a darshan again. I prayed to the devi to ignore prayers, if any, made by the missus for more offspring. We then followed Senior Lalje’s TVS moped through the town to Parner road, where their house is located. The farm is not too big – probably an acre or an acre and a half. There is an odha, which had irrigation canal water flowing through it, that is next door. (It flows alternate months.) We had to cycle on the bund that marks the boundary of the odha to reach the house at 1730 hrs.

Senior Lalje is 74 years old. He stays with his 70 year old wife and two dogs on the farm. The dogs were both on rope leashes – which made them more aggressive than the usual village canine. Even the dog lover missus had to stay away from them. Sr Lalje used to stay with his two brothers in the ancestral house. But he got fed up with the drinking habits of the extended family – and two years ago built a house in the middle of his small farm.

We were taken on a tour of the farm. We started with the 20 ft dia well. It had water at a depth of just 15 ft. Probably the odha next door ensured that the water table was not too low. Most of the farm had wheat growing in it. Though Sr Lalje uses a simple Nokia type mobile phone, technology has started making inroads into agriculture. Earlier Sr Lalje used to move around with a back mounted sprayer, but now a local lad comes with a drone to spray insecticide on the Lalje fields.

Every farmer also has small patches of land where he grows stuff for his own consumption. The Laljes were growing onion, garlic, chana and a few more dals for their domestic consumption. Sr Lalje supports Yogita’s family in the city by sending across farm produce. Ate some fresh harbara plucked straight from the field. I had ignored a warning to wash the harbara before eating. I discovered that there is a citric coating on the outside of the pods – which irritates the lips. Most of these patches are semi-organic, in the sense that though the farmers use inorganic fertilisers, they avoid spraying pesticides on this patch. Methinks that there is a good market if city folk can make these patches bigger by paying premium prices for such produce.

I have been reading Abhijeet Banerjee’s book – Poor Economics, where he talks about the diversity of professions in poverty. A poor household has an average of 4 professions pursued by its members. By this yardstick, the Laljes, at 3 professions, are above the poverty line – but only just. Mrs Lalje works as a farm labourer. We realised that she had taken the day off to prepare dinner for us. Sr Lalje doubles up as a poojari in the village temple. Thanks to the offerings at the temple, dinner had a generous dose of coconut.

One wonders about the divinity of guests in Indian culture, even amongst the poor. What was touching was that the Laljes had even purchased a few bottles of mineral water, afraid that their well water may not be to the liking of city folk. We refused to touch the bottled water; I survive a dozen train journeys a year on railway platform water.

There was no electricity when we landed up. Nigoj villages are supplied with electricity from 1100 to 1600 hrs. This three phase electricity is used to operate the farm pumps. Leopards have helped rural Maharashtra in many ways. They have significantly reduced the stray dog population. And they have also forced the government to supply single phase power from 1800 to 0600 hrs. This is to ensure that houses and roads are well lit when the leopards are on their nocturnal rounds. As cyclists, we must thank the leopards on both counts.

Having skipped lunch, the hungry cyclists requested a pre-sunset dinner. Incidentally, the human body doesn’t synthesize insulin after sunset – so the ancient wisdom of finishing dinner before sunset has some scientific basis. The Laljes did not join us for dinner – as it was too early for them. The simple but extremely yummy dinner had 4 items on the menu: bhakri, kala rassa, maswadi and kollam rice. Maswadi is besan rolls filled with a stuffing of coconut, peanuts, and til seeds. The rassa was an onion-garlic-coconut curry. Had double helpings of everything.

Lalje’s daughter, Yogita’s sister-in-law, is married into an agricultural family – her husband’s village is about 20 km away. Marrying off a daughter in a relatively close by location is an insurance policy for the Indian parent. The distance is important as local climates differ – and crop failures may not happen at the same time at the two locations. The daughter is much better off – as her husband has a much larger land holding. They have two sons – the elder is a mentally challenged kid. The families visit each other every few months.

A photographer’s motorcycle trailer

After a 10 hour restful sleep at the hotel, we had a leisurely breakfast at the hotel – poha and chai, and left at 0815 hrs. Discovered that in addition to onion and sugarcane, there is some acreage of corn and horse-grass – used for cattle fodder. The return journey always has fewer adventures. We made the same pitstops.

Maithan Rajwada

At Maithan, as we sipped our no sugar milk chai, we asked the Hotel Rajwada proprietor about the Rajwada next door. It is an old structure built on a small hill. I guess forts and palaces always like altitudes as it helps to keep an eye on their subjects and invaders. The Pawar family continues to stay there – and unlike our Baramati friends, this family is not into politics. Having said that, their blessings count in elections.

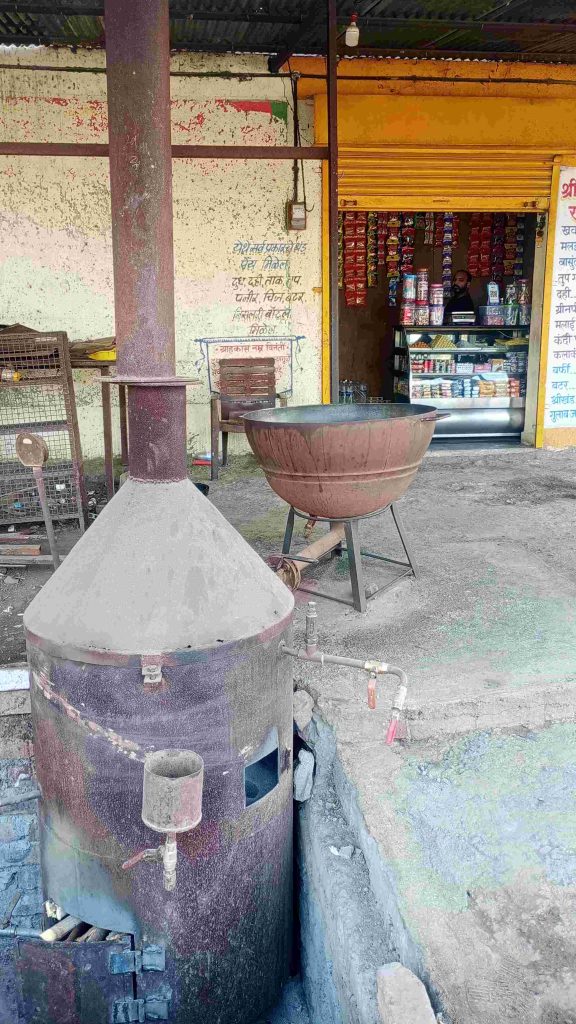

Khoya Kettle

Stopped at a local khava/ khoya shop to admire the boiler and kettle used for making khoya out of milk. The khoya is made in batches. 5 liters of milk yields one kg of khoya in one hour of heating. I tried working out the economics. 1 kg of milk is purchased at Rs. 40 a liter. Khava retails at Rs. 280 per kg. The boiler to produce steam for the kettle is wood fired. Firewood is bought at Rs. 4 per kg, and a typical day requires Rs. 500 worth of wood. All labour is family. Assume that they do about 8 batches a day. So revenue is 8*280 = 2240. Milk Costs are 1600. So gross margin is around Rs. 340, just about enough to meet the labor cost of the family. This reminded me again of Abhijit Banerjee’s Poor Economics.

We had a 30 min charging break at the same Shikrapur hotel. We shared a misal and wada – and to add some fibre in the diet , we gulped down a few bananas. The ride back from there was quite mundane. Most highways crossing a city have been made without service roads. So wrong side driving is the norm, not just for motorcycles and scooters, but also cars and lorries. This ensures that the cyclist, who is usually at the receiving end of these American style drivers, is on the alert all the time. I remember escorting some mentally challenged kids on a cycle rally – and how one of the kids had a fall thanks to a wrong side biker – which damaged yours truly and his cycle – ending the Pune Mumbai rally for me – even before we had exited Pune. If NHAI does not have the budgets to do service roads – they can start by building them half a km on either side of a break in the median road divider.

Having preached so much about this, let me confess that at Wagholi, I was myself on the wrong side of the road to escape a 1 km long traffic jam. This is a regular feature on this stretch – and for a cyclist getting caught in a jam is not too good for the lungs. The missus on her electric cycle followed the rules – and took 15 min more to clear the jam. We had a farewell sugarcane juice party just short of Kharadi – where Giri took the bypass to head home. We reached home at 1430 hrs.

That evening, as we had dinner, we remembered the Laljes. In hindsight, we probably should have stayed over at the Lalje’s place. The tariffs would have gone a longer way for them than the proprietor of Nisargraja hotel. As the sun set and we ate our urban dinner of rajma and greens, we reminisced about the lessons learnt from Sr Lalje – and how dignity and poverty can co-exist.