A three member team spent a day being trained to take the P4C program with school students. The venue was Aryawrat Society near Ghotawade Fata. Venue was courtesy Archana Joshi, who owns a plot in the society. The Joshi family has been benefactors for this program by also offering the hall at Ved Vihar Society, Chandni Chowk. This is the society they stay in. We landed up around 1145 hrs – and were happy to find that the hall was an open shed – overlooking a beautiful lawn.

Got to know a little bit more about Paddy in this session. He has done his electrical engineering – and was working as a Production Manager before transforming into his current avatar as a philosophy trainer. This builds on his volunteering work with a rural school in Karnataka which was serving the migrant farm labour community. In order to inculcate good thinking in a child it is important that she is curious. He used an interesting analogy over here. An infant feeds only when she is hungry. Our body has automatic mechanisms to stimulate hunger, but probably none to stimulate hunger for knowledge. Our job as teachers is to work on this stimulation.

Paddy uses dialogue as an excellent tool for this stimulation. He started the session with a stimulus: Only 2% of the people who were in the merit list for grade 12, had also been in the merit list for grade 10. Why? The beauty of the dialogue technique is that the teacher does not have to rehearse the answers to the question she asks. All that is required is to be open to ideas that the students contribute. In the specific case of the board student, we felt that probably a different set of skills counts for 12th vis-à-vis 10th. Some of us felt that the discussion of marks itself is meaningless, as it does not count too much for later life success. Others talked about how school may be common, but homes are not. We were nudged towards thinking about how lost all of us are in our routine, that we don’t think too much of our goals and our roles in life.

This set stage for the introduction of the objective of the P4C program – To develop a community of enquirers. Though some of us had doubts about whether everyone can ask questions all the time, the very presence of the doubts indicated a success of the program. For the first stepping stone in this community development, is questioning your self. An infant does not take even gravity for granted, yet an older child or an adult will accept almost every rule that society thrusts upon him without questioning. We need to take this adult/child more towards Doubt in the continuum between trust and doubt. A good metric in assessing the questioning skills of our students would be: are students asking questions that make our teachers think.

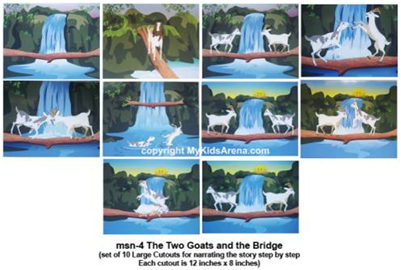

The more our kids question, the more they learn how to learn. The more independent thinkers they become. The kernel of a typical P4C session is an experience, story or an activity. If an experience is used, it should be a neutral one – not drawn from a participant or a teacher’s life. The formats of presentation can vary – for example, a story can be presented through picture cards. Students can then be asked to build the story. Here is an example of a picture story:

The small disadvantage of using a picture story is that it does not help in building imaginative skills of students.

Moving on to the dynamics of organizing a session. The starting point is always a calming down exercise. In this exercise students are first made to close their eyes. Since almost 75% of the stimulus a brain receives is visual, the eye closing serves to focus attention on the other sensory organ inputs. The teacher needs to help direct the brain towards the other senses. The student sits upright with both feet planted firmly on the ground (I myself prefer bare feet on the ground.) The first sense to explore is touch. Sense how you can feel the chair that you are sitting on. Sense the cloth of your uniform touching your body. We then move on to sounds. Hear the sounds of your body breathing, hear the sounds in the class – of the wind coming in through the windows, the fans whirring. Hear the sounds outside the class – vehicles moving on the road outside. After about 2 minutes ask students to slowly open their eyes. Then ask them how they feel? During the session you can ask this ‘how do you feel?’ question often. It serves to reinforce positive feelings. You can also ask “What did you think of?’ This is to check on students who are still not in the zone. Divergent thinking needs to be discouraged.

The first part of the session is usually a round-up of a thinking assignment that was given after last week’s session. Some teachers put the ‘Thought for the Week’ on the board or as a poster on the classroom wall to serve as a reminder to students to do this thinking. The starting discussion is important because it tells us whether students have actually been up to the thinking task through the week. They offer evidence of what worked – and what did not. The discussions reinforce the last lesson.

In our demo class, Paddy used an activity as a kernel. This was a role play – where some of us had to become shepherds and the rest sheep. The run time of the activity was 45 minutes. Instructions were written down on a card and presented to groups. The first thing that Paddy did was to ask ‘Who wants to volunteer to be the leader (Shepherd)?’ In our class, Archana and Anita volunteered. The two shepherds were then asked to choose their own flock in a way that the sheep were distributed equally between groups. Each group then separated out and were told to follow the instructions of the card and come up with a plan to execute the task given on the card.

The card instructions were that the group had to use very simple sounds like – whistles, claps, and beating of sticks in order to get the sheep into an area which was designated the pen. The sheep could be placed anywhere in the play area. The shepherd had to stand at a designated area and guide the blindfolded sheep. Each group had to come up with their own rules that when used would help the blindfolded sheep move into the pen. Surprisingly, both the groups that were formed came up with very similar rules. In order to ensure that as a teacher you have as much fun with this exercise as we did, I will not take you through the rules we used. But as a moderator a tip is that you can use objects to delineate obstructions and the pen in the ground.

At the end of the activity the participants got back to the round table format that is usual for P4C sessions. Paddy then started his questioning. ‘Why did we do this activity?’ ‘Why did you choose to be a leader / follower?’ ‘When the pre-activity group rule discussions started, did everyone contribute?’ ‘Did the group have a post-event discussion?’ (This was a close ended question because neither of the groups had had this discussion. He made us feel guilty as hell for being poor learners of learning.) ‘What did the other group do wrong?’ ‘What is responsibility?’ ‘What should be the thought for the week?’

Paddy gave us tips on how to make the game more interesting. Having two groups working in parallel on the ground. Ensuring that other groups sheep have to be avoided. Converting one of the sheep into a fox. And he also advised that if there are multiple ideas for the ‘Thought of the week’, then the facilitator needs to zero in on one idea that they think is the most relevant to the activity.

A few word on rules related to discussions. In the case of our session, Paddy had got along placards with rules written on them. He showed them to us before we started the session. In case any one was not following rules, he only had to raise that placard for us to get the point. This saved time for both students and teacher – and at the same time did not seem to hurt the ego of the offending party. One interesting idea that Paddy introduced was to have a separate session (preferably the starting one) where the class discusses the importance of rules – and ends up agreeing on what rules are important for the class.

Here is a rough plan for the Rules class. Introduce the concept of rules and develop briefly. Here are questions that will help. Where do we find rules? Why do we have rules? Are rules always useful? Why? Should we always stick to rules? What would life be like without rules? Break children into small working groups depending on their ability to co-operate. Small friendship groups are ideal to start off with. Explain to the class that there is going to be thinking about how we should work and talk together. By the end of the session, the class would have made up a set of rules, especially for them.

To start off, they are going to look at some possible rules and with their partner group decides which of them would be helpful or not helpful for the class. Here are a few sample rules:

Talk about what you are going to do after school

Make silly noises

Interrupt when the teacher is speaking

Shout out when you would like to say something

One person talks at a time

Put your hand up if you would like to say something

Look at the person who is talking

Cooperate with each other

Everyone takes a turn

Listen to the person who is talking

Sit facing each other

Stop at the teacher’s signal

Stay on the task.

Once the group has discussed each rule, they should place it on the chart according to its importance. Before they are given the materials, the group should decide on a strategy for carrying out the task. How will they manage the cards, How will decide where the card goes, Who will go first etc.

Distribute the materials and allow groups to carry out the task. Circulate and ask Groups for reasons for placement of cards. If group complete task, they can use blank cards to make up some cards of their own and place them on the chart. Alternatively a floor set of rules may be done with the whole class.

Once cards have been placed, each group should take the best rules and put them in order of importance. Again they should have reasons for this. Groups report back and as a class decide on the best rules. Teacher can add any rule she thinks are important. After all, she is also part of the class.

Review lesson how well did children work? What was learned. Discuss a possible thought for the week. (Hopefully to do with rules and their effect). Display the thought with the rules the class has decided on. Class could illustrate them. Children should sign an agreement and display it along with the rules, illustrations and thought for the week.

He also told us of an interesting exercise that they had done using this template in the rural school. Coming from the low income, socially backward background, most students of the school used language which was plentiful in abuses. So one day the class had a discussion on abuses. It started by listing down all abuses on the board. And then there was a discussion on what abuses were acceptable – and what were not. They realized to their consternation, that most were not. Yet, they were also troubled, that in the absence of the function of steam-letting out which is served by abuses, there would be physical violence. So they then came up with a new list of acceptable abuses. Most of the happened to be animal names! They also came out with a consensus punishment for the use of abuses. The implementation is quite innovative. There is a register outside every class where anyone can record details of the ‘abuse’ incident. Once the incident is verified, the student takes up the punishment – which is typically watering the garden..

We ended the session with an evaluation. Evaluations are important as they reinforce learning. Paddy typically picks up one rule to focus on in a session. He uses his standard trick of raising or lowering hands in order to check with the class as to how much of conformance was there with the rules. Sometimes this evaluation is also done by a specially invited observer. Form for evaluation is at the end of the note. The evaluation can serve as a guide map of future focus areas of a class.

Cees Comment

I just want to comment on one sentence from this article. That is this one: Our body has automatic mechanisms to stimulate hunger, but probably none to stimulate hunger for knowledge.

That sentence surprised me strongly. All children are very curious right from birth. There is nothing that they want to do more than explore and discover. But in practice adults take away the drive for children to learn. Take away the freedom to learn. Adults try to mould children. Expect children to respect adults without showing any respect to them. Adults feel the need to discipline children. In whose benefit? It is not that children are not interested in learning. No we kill their eagerness to learn.

In one of the Dutch articles on CAM I read: Brains are created to survive, not to learn by heart. We have to challenge the brains of our children in a positive way by offering them the opportunity to discover and by asking them open questions. Only than they will learn to think critically and creatively. They are challenged to make their own well thought choices. That was we will see adults who are able to think independently and who won’t blindly follow others.

Excerpts from ‘Thinking Through Philosophy’ by Paul Cleghorn and Stephanie Baudet

‘If I meet a hundred-year-old man and I have something to teach him I will teach;

If I meet an eight year old child who has something to teach me, I will learn’.

Chao-chou

9th Century Zen Master

When people are first introduced to the idea of philosophy with children they are often dismissive. What is the point of teaching children philosophy when the curriculum is already overcrowded, and to what purpose? They envisage lessons on existentialism, or the life and thoughts of Schopenhauer. The first point to make therefore, is that this is practical philosophy – it is about the process, not the teaching of facts. We are not interested in facts about Kant, Wittgenstein, or even Socrates, but we are interested in the process of exploring philosophical questions through Socratic questioning. It is the dialogue that is important!

The crux of such a programme is dialogue. This is much more than mere conversation, and offers the exciting possibility that one’s own ideas and perceptions may change in the process. To use the jargon, this process begins to develop a ‘community of enquiry’, wherein teacher and pupils learn and develop together. Following the introduction of a stimulus such as a story or poem, philosophical questions are formulated from which the dialogue is derived. The key to developing good dialogue is the skill of the ‘facilitator’ in asking good, open-ended questions and encouraging the children to develop the same. These will include such questions as:-

- Can you say more about that?

- What makes you say that?

- Do you have any evidence for that view?

- How do you know that?

- Why? Why? Why?

- Is it possible to know if that is true?

- Does anyone else support that view?

- If…then what do you think about…? and so on.

It is through this process of dialogue that thinking skills are developed. These include:

- Information Handling – processing skills about analysing, interpreting, locating.

- Enquiry – posing and defining problems, planning, predicting, testing conclusions.

- Reasoning – giving reasons for opinions, making deductions, making judgements informed by evidence.

- Creative Thinking – generating ideas, being imaginative in thinking, being innovative.

- Evaluation – evaluating what is read or heard, developing criteria for judging.

As parents, as a society, we are not only concerned about how smart our children are, but what kind of people they grow up to be. When children explore moral and ethical questions, thoughts, behaviours – there opens up the possibility of even seeing the causes for these. This is a very empowering process because it brings the youngster to a point where choice is possible instead of habitual behaviour. This is real learning. It begins to have an effect on the whole community, whether that community is a family, a class, a school, or indeed society itself. For example, how do we get a just society? Imposing rules (laws) from the outside doesn’t seem to work too well! It is better when the regulation comes from the ‘inside’, with each citizen being self-regulated through having the self-knowledge to make informed choices!

As very young children begin to explore the world around them they touch, smell, and even taste everything and anything they can get their hands on. As they move into the world of language they begin to ask questions about everything – why, why, why. There is a natural spirit of enquiry that seeks to know ‘What is this creation and what is my relationship to it?’ Little philosophers abound! Unfortunately, in most cases this natural curiosity is largely knocked out of them by being ignored or told not to ask silly questions! The philosophy programme with children seeks to restore what is in fact absolutely natural, and build on this as cognitive development allows – then a ‘community of enquiry’ is born! In this, children learn about the process of learning and also about themselves as learners.

A community of enquiry has a rational structure and a moral structure. The former is about how to go about exploring ideas through dialogue and is detailed in the criteria of part ‘B’ of the evaluation form at the end of this section. It includes such aspects as ensuring that participants:

- Ask open and inviting questions

- Give evidence and examples

- Make comparisons

- Summarise and evaluate

- Seek clarification

The moral structure includes the application of emotional intelligence and could be called the ‘spirit of enquiry’. It also includes the rules of behaviour necessary for a group activity such as one person being allowed to speak at a time. Further detail in part ‘A’ of the evaluation form includes ensuring that pupils:

- Focus attention on the speaker

- Don’t ‘put down’ others

- Are not forced to speak

- Respect others’ views

- Are truthful

- Are open minded

Pupils should sit in a position in which they can see each other, and this very much depends on the layout of the classroom. Some people use a circle, but with a whole class this can mean large distances between people (i.e. from one side of the circle to the other) and this is not helpful in developing a supportive, inclusive atmosphere. A horseshoe, semi-circular shape is often useful. The teacher’s role is often called ‘facilitator’ in the current jargon, and this is to show that it is not a traditional one of imparting knowledge or facts, but one of helping the process of the dialogue. This is done through being an active participant and at the same time stimulating the process by:

- Focusing attention on important points.

- Modelling good questioning, for example, by asking for clarification, reasons, evidence etc.

- Encouraging pupils in appropriate behaviours, such as how to respond to each other, to listen to each other, and so on.

- Rewarding positive contributions with praise.

- Not being content with conversation.

- Directing the discussion towards Truth. *

The teacher’s role is a dynamic one – sometimes being an ordinary participant, sometimes guiding a pupil to deeper involvement, sometimes ensuring that the agreed rules are adhered to. It takes practice!

THE STRUCTURE OF EACH PHILOSOPHY SESSION

In this section the structure of each philosophy session is described, and the details of each element.

THE FOCUSING EXERCISE. This is a simple but extremely powerful exercise that helps people focus their attention and be ‘in the present’. Its simplicity is its strength and also its weakness. It is easy to do, but also easy for children to think they are doing it when in fact they are not.

The exercise consists of simply ‘giving’ attention out through the senses for two or three minutes. This creates a highly alert yet peaceful condition. For the short time (literally two minutes) that it takes to do it, in value for time it is probably the most powerful aspect of the programme! The first purpose is that of calming – a physiological harmonisation takes place in which breathing and heart rate slow and there should be mental and emotional calmness. This is a good state in which to be able to think! Secondly, there is the notion of ‘giving’ attention. Instead of our levels of wakefulness (consciousness) being largely haphazard and habit driven, the individual begins to have a choice, and to exhibit control over this. This is very powerful in relation to raising attainment and exhibiting emotional intelligence. This very important technique of learning to ‘be in the present’ or ‘be here now’ was reported in a well-researched article entitled ‘Mindfulness’ in the British Medical Journal of November 2001.

To do ‘the exercise’, ask children to sit in an upright position with straight back and feet flat on the floor. Initially, explain the reasons for doing the exercise. Tell them that they can use it whenever they choose – before a test, doing a piece of writing, when they feel angry or upset, and so on. Be sure to include before a football game! For athletes to be ‘in the zone’, that area of peak performance, they must be in the present and fully focused. Children should listen to the sound of the teacher’s voice as the instructions are read out and should try to follow, focusing only on what they themselves are doing and not on anyone else.

“First give your attention to the sense of touch. Feel the weight of your feet on the floor

. . .Your body on the chair . . .Your clothes on the skin . . . Pause. Now, using sight, and without naming things in the mind, see colours . . . shapes . . . the space between the shapes. Pause. Now using the sense of hearing, hear any sounds close at hand (e.g. within the classroom)

. . . now let the hearing gradually run right out until the furthest sounds can be heard . . . Pause. Now try to hold that awareness for a few moments.”

It is important that children do not just sit there daydreaming – this is a conscious activity. A short period of questioning children on the experience can be useful sometimes, but remember it is not about hearing a bus, a bird and so on, but rather developing a growing awareness of where their attention was – was it on the looking and listening or on thinking about what they were going to do after school?

Sometimes in the Teaching Notes attention is drawn to particular aspects of the exercise. This is to provide variety and also to deepen awareness of the technique. Many teachers find it useful to practise the exercise daily and at times when the class needs to settle or focus attention.

LINKING WITH THE PREVIOUS WEEK

This is simply good practice and reinforces in the mind what has taken place the week before, thereby strengthening memory. It also provides an opportunity for children to bring forward new evidence and experience from during the week. Thinking is not something that only takes place on Wednesdays from ten until eleven!

PAIR/GROUP WORK

This provides an opportunity to check that children have understood the literal meaning of the story or poem, and more importantly, is where there is a planned focus on one or more of the thinking skills. These are built into the programme. Also important about this stage is that it is very ‘inclusive’. Children who may not initially speak in a whole class forum can gain confidence that their ideas are important and accepted in a small-scale setting.

THE STIMULUS

The story or poem is read aloud by the teacher.

DIALOGUE

The key to the whole programme. This is the Socratic method of questioning or ‘dialectic’. Prof. Matthew Lipman says this is not ‘mere’ conversation, but ‘an inquiry, an exploration of ideas – a quest. It follows a line of investigation like a detective’. The ‘Questions for Thinking’ are used to stimulate this process, but it is important to note that these are not to be slavishly followed through to the end if the dialogue is flowing. The section on ‘Questioning’ in these notes will help build the skill of being a good facilitator of a dialogue. It is not to present yourself as the expert in philosophy (and it is assumed that you are not), or yet to move the group to think as you think. It is to coordinate and enhance the dialogue by modelling open questioning, by encouraging all to take part, by not being content always with first answers and knowing how to allow the child to think more deeply by further questioning. Look at the criteria in the ‘Assessment of a Philosophy Session’ for further examples.

Dialogue is important because it stimulates a deeper engagement between pupils and teacher and can take learning to a deeper level of understanding. It requires the teacher to move from being a dispenser of information to a facilitator of learning – the method can be used to great effect across the curriculum. Dialogue stimulates thinking and emotional intelligence, bringing with it self-confidence.

CLOSURES

These are brief ways of closing the dialogue and in essence, provide a variety of ways of drawing the attention of the children to how their thinking has progressed during the session.

THOUGHT FOR THE WEEK

Each week a practical idea drawn from the theme of the story or poem is highlighted to provide some ‘homework’. In the main it is looking for evidence in real situations of an aspect of the theme. This should be encouraged but entirely natural and unforced! Nothing will put children off more quickly. It is useful if the ‘Thought for the Week’ is displayed on the classroom wall for reference and as a reminder.

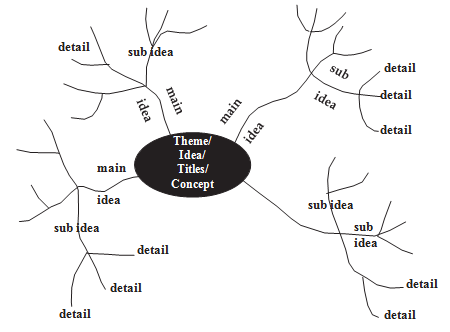

THINKING MAPS

‘Thinking maps’ are also known as model maps, webbing maps, learning maps, and various other names including at least one that is registered copyright!

Thinking maps are just that – a guide to our thinking on something, whether as a study guide to remember a piece of work (book, concept, area of study, etc.), or as a method of showing development of an idea or even helping in the actual process of developing it. Thinking maps help us remember – and remembering means just that, remembering. That is, putting back the ‘members’ (parts) or making a unified whole out of the diversity of the different ideas. This implies also a ‘making sense of’. A thinking map is a visual organisation of ideas that shows both the overall view and the detail.

A thinking map not only brings clarity to the central idea, but fits itself to the individual’s thought patterns as it is constructed. They may be used for reviewing work previously studied, finding out what is known about something, and as a tool to explain something to others. They are also useful in developing lines of thought or concepts.

To introduce thinking maps it is best to first talk through the concept with pupils, then show them one fully constructed, such as the one given above. Next, collaboratively build one on the board so that children see the various steps in construction. Use a theme or topic recently studied or well known to the pupils.

When constructing a thinking map:

- Begin by writing the theme, title, or main ideas in the centre of the page.

- Put in the first radiating arms by writing in the main ideas that come to mind.

- Develop these, one at a time, by writing in the sub-ideas, then the detail.

- If other major ideas occur, write them in and develop them.

- Some people like to use colour (e.g. a different colour for each idea) or draw little pictures. Each individual should decide whether this is important to them, and use the devices if they help.

For the map to be of use, once it is constructed it must be actively and consciously used using language to ‘tell the story’ of what it shows. That is, instead of a cursory glance, each branch must be described right out through the main ideas to the sub-ideas and the detail. This can be done silently ‘in the mind’ or out loud. Each repetition of this process reinforces what the map contains.

Philosophy With Children

Observation Sheet

In observing a philosophy session, jot down strengths, weaknesses and points for discussion. Remember to note – good comments by children; evidence or reasons given by children, linking of several ideas by an individual or several people, range of questions by children, has the group ‘moved forward’ through dialogue?

The Calming Exercise:

The Stimulus:

Individual/Pair/Group Work:

The Enquiry Through Dialogue:

General Comments:

Assessing Classroom Dialogue

Class: Date:

Duration:

| Behaviour | Tally Marks | Total |

| Pupil 1. Occurrence of pupils asking a question. | ||

| 2. Occurrence of pupil supporting their view / opinion with a reason. | ||

| 3. Occurrence of a pupil agreeing or disagreeing with the view of another pupil, and giving a reason. | ||

| 4. Occurrence of pupil offering a reviewing or evaluating comment. (See ideas under ‘ S k i l f u l Q u e s t i o n i n g ’ section). | ||

| 5. Occurrence of pupil directly addressing another pupil. | ||

| Teacher 6. Occurrence of teacher asking a question requiring a one word or factual response. (Not useful for dialogue). | ||

| 7. Occurrence of teacher asking an open- ended question. (This includes follow-up questions). |

Developed, with permission, from work by S. Trickey

SCALE:

Evaluation Form For Philosophical Enquiry

A. THE ETHOS OR SPIRIT OF ENQUIRY

(Listening and Responding)

0 = hardly ever, 1 = some, sometimes 2 = most, most of the time 3 = almost all the time

| 1. Did people focus their attention on the speaker? (Attentiveness) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 2. Did people avoid interrupting or rushing the speaker? (Patience) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 3. Did people encourage each other to speak? (Altruism) (e.g. by smiling, taking turns, etc.) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 4. Did people respond to the previous speaker? (Responsiveness) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 5. Did people respond to the main questions being asked? (Tenacity) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 6. Did people keep their speeches brief and to the point? (Relevance) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 7. Did people recall others’ ideas and put their names to them? (respect) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 8. Did people try to build on others’ ideas? (Constructiveness) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 9. Did people listen to ideas different from their own? (Tolerance) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 10. Did people show a willingness to change their minds? (Openess) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

SCALE:

B. THINKING TOGETHER

(Questioning and Reasoning)

0 = not observed, 1 = observed at least once 2 = observed now and then 3 = observed often

| 11. Did people ask open and inviting questions? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 12. Did people ask for clarifications of meaning? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 13. Did people question assumptions of fact or value? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 14. Did people ask for examples or evidence? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 15. Did people ask for reasons or criteria? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 16. Did people give examples or counter-examples? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 17. Did people give reasons or justifications? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 18. Did people offer or explore alternative viewpoints? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 19. Did people make comparisons or analogies? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 20. Did people make distinctions? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

2018 Mar, Session by Padmanabh Kelkar, Philosophy for Children

We started with a very interesting ice breaking exercise. Padmanabh asked all the kids to make a lot of noise. The level of noise was directed by him by raising or lowering his hands. The next ice breaking exercise was to wash your hands with air. The last activity was to put your hands together in a namaste. Close your eyes. And based on instructions press and relax the hands. Next you take them apart and you get them back together. Padmanabhan did the session by getting feedback from students about how they felt after these activities.

Next he moved on to a story session. Started by asking students: ‘How would you like to listen to a story?’ Every student raised his hand. Then Padmanabh went on to narrate the story of the monkey and the crocodile.

The monkey and crocodile were the best of friends. The monkey lived on a mango tree close to the river. The crocodile one day invited the monkey for a birthday party of his wife. The crocodile’s house was in the middle of the river. The monkey could not swim.

‘No problem, my friend’ said the crocodile. I’ll take you on my back. The monkey jumped onto his back. Halfway through the river, the crocodile mentioned to the monkey. ‘Actually, I lied to you. The king of the crocodiles is very sick. His doctor has told him that he will only recover If he gets to eat the heart of a monkey. So I’m taking you there.’

The monkey started thinking. He told the crocodile: ‘But there is a problem my friend. I have left my heart back on the mango tree. I also want your king to be saved. Let’s go back to the mango tree and I’ll pick up my heart and come back with you.’

The crocodile agreed and they went back to the tree. The monkey jumped on to the tree and retorted: ‘What kind of a friend are you? You wanted to kill me.’

The story was done with a fair amount of interactivity. For example questions would come in like what happens when we take out a heart. After the story telling students were broken into groups of 3 and they were asked to discuss why did they think this story was told to them.

Student responses:

To entertain us.

Don’t lie to your friends

Don’t lie

Don’t trust others

Don’t underestimate anyone

The story was then revised again by ferreting out the details out from the students by asking questions: What did the crocodile tell the monkey? Is lying good? Did the monkey do the right thing by lying? An interesting kaizen: Those who want to answer, don’t raise your hands, but sit with your hands folded.

We then moved on to the philosophical discussion: When do we lie? The answers were interesting:

When we are in trouble

When we want something.

To escape punishment.

When we make a mistake.

When we don’t want to do something.

To make fun

Sometimes we also lie when you want to threaten others

Then another question was asked by the moderator: Do we lie to make others happy? Students came up with responses that even if the food cooked is bad, they still praise their mom.

Next moderator question: How do you feel after you lie? The response was: we feel bad and possibly afraid. One suggestion from students was that we should lie to friends not parents. Because parents can scold you. One student confessed that when they have a toilet break he goes to play. And when the teacher asked him why he took more time. He mentions that he had to go to number 2 in toilet.

The assignment that was given to students during the week was to ask observe when did they lie? When is it bad to lie? One week later another session is planned where students will discuss their experiences.

A very interesting way of taking feedback was we use the same hand tricks that had been used at the start of the session. An upheld hand meant a good session; a horizontal hand meant a bad session; a hand held down meant a bad session. They were asked to close their eyes for this exercise. Only one student give an average report the rest thought it was great.

Notes on School for Thinking, Meet by Padmanabh Kelkar, Feb 2018

Padmanabh is Meher Gadekar’s friend. Meher forwarded me an invite to attend a meet to discuss an idea being pursued by Padmanabh – ‘The School for Thinking’. I and Pinki landed up on Sunday evening at Ved Vihar Community Hall, near Chandni Chowk.

Cees Tompot was one of the speakers. He is from Holland. He chairs Yojana Projecthulp, an NGO that has been working with Yerala Project Society for many years. Cees started off as a missionary in Africa. He has since got out of religion, but maintains his missionary zeal. He worked with the Tax office in Netherlands – volunteering to work with Yojana after work hours – and a full timer after retirement. http://www.yojana.nl/English/index-english.htm

Padmanabh showcased Yojana’s work at Jailihal – located near Bijapur. Yerala Project Society has been working there for many years. Jailihal is located in a wind shadow region – and is drought prone. Most of the people there find employment in neighbouring areas during sugar cane harvest, as migrant labour. As a result of this temporary migration, education of kids was not working out. YPS has started a boarding school for the villages in the area – and arrange for the kids to stay for 6 months in a year – when the parents are out. Some of the interesting projects that they have done in school:

They maintain a bicycle bank with 500 bicycles in all. They run a science lab which has been working in collaboration with Nemo Science Center, Netherlands. (https://www.nemosciencemuseum.nl ) and Technopolis (http://www.technopolispark.nl/ )

The curiosity (Curi-O-City) center promotes enquiry based interactive learning. The local touch is when students catch snakes and observe them for a few days before setting them free. They have a Water Lab where students work out experiments with pumps and pipes. They also run a 6 acre farm for student projects. Gender equality is promoted at the school by innovative games like Blindfolded catch ball. Here is the society website: www.yerala.org

Padmanath Kelkar is the local coordinator for YPS projects for Yojana. Along with his work for YPS he is also deeply involved in education. Here is an interesting viewpoint he has on parent teacher cooperation. There has been usually an abdication by parents on matters related to education of their children. Whenever the kid asks them a question – they reply back – ‘I don’t know. Ask your teacher.’ Such children have usually been conditioned to only communicate with their mother if they are hungry or with their father if they want money.

An interesting discussion was held on young kids who like making houses by hanging curtains around a bed. One architect friend of Padmanabh reasoned that this could probably be because they don’t consider their own house their own. So they have to build something different. Given this alienation and problem in communication, it is not surprising to find that when this child grows up he tells his parents ‘You shut up; You don’t know anything in any case’.

There is one very interesting workshop that Padmanabh does: RTTS. Reading To The Smallest. A parent or a teacher reads out a story to her child. Even if the parent is not well educated, she can still look at pictures in the book and imagine what the story could be like. In this exercise a lot of attention is paid to the student. This is a great exercise for teacher-child or parent child bonding. There is a workshop in Pulgaon on RTTS on 14th and 15th February.

Padmanabh also teaches a very interesting course called Philosophy for Children. Some snippets of his and his Dutch friend Jaap Schouten’s teaching philosophy.

‘Nothing is 0%; Nothing is 100%.’

‘To learn anything it is important to accept: We don’t know’. Ignoramus from the book Sapiens written by Hariri

‘A student does not care what you know until he knows you care.’ Jaap Schouten

‘Experience is not the best, but the only way, to learn.’ Jaap Schouten

‘You have to believe in the possibility of change. Only then will you be able to create change.’

‘An outsider saying something is always more valuable. Which is why exchange of teachers between schools is a great idea.’

Questioning, often is forbidden in schools. Teachers feel questions to be an attack on their teaching capacities. “if you have questions, you express that you doubt my teaching capacities.” In most western schools questions are stimulated. Here questions are seen as signs of interest and a result of good teaching.

Children who lost their individuality also lose the sense of individual responsibility. They learn to hide behind the group and behind traditions. And thus often horrible social injustice like feticide will be transferred from generation to generation.

Cees quoted Narayan Murthy: “In the West, right from a very young age, parents teach their children to be independent in thinking. Thus, they grow up to be strong, confident individuals. In India, we still suffer from feudal thinking. I have seen people, who are otherwise bright, refusing to show independence and we need to overcome this attitude if we have to succeed globally.” According to Padmanabh, some of the Critical Thinking problems that Indian schools face:

- There are no discussions in class. Unless students are frank, discussions will not happen.

- We follow blind traditions. We look forward to our teachers / elders too often for advice. We need to develop critical thinking skills of students. It is independence of decision making that leads to job security.

- We are happy to hear. Learning By Doing is the earliest way of learning for mankind. The hunter gatherer was asking herself: Is this fruit edible? How do I escape the Lion? How do I catch the rabbit? Doing and Learning.

We consulted many educationalists who all told us that there are two ways only to help children understand. The first one is to stimulate them to ask and the second one is to learn from experience.

As Confucius already said: I hear and I forget. I see and I remember. I do and I understand.

We ended with a very interesting demonstration of Philosophy for Children, where we did a roleplay of kids in a classroom. We started by removing our footwear. Pressing the feet to the ground. Closing our eyes. And concentrating on the sounds around us. This is the Calm Down exercise. The next exercise was a follow up of what had been discussed in the classs in the last week. For example the topic of discussion could have been ‘What is Truth?’ So what have been the implications of untruth at home.

This was followed by a story. A king had three daughters. One day, he called all three of them and asked them: how much do you love me? One of them knew that the king was very fond of gold. In order to impress him she said I love you as much as I love gold. The middle daughter knew that all the coins in his Kingdom were minted in silver. She mentioned to him that I love you as much as I love silver. The youngest surprised the king by telling him that she loves him as much as she loves salt. The king asked the youngest daughter why did she trivialiase her love. He was very angry with her. The youngest daughter left the room and went to the kitchen. She told the cook: ‘Please do not put any salt in the food that is made today.’ The king realised his foolishness during lunch time.

This was followed by a question and answer session. Who do you think loved her father the most? The rules for answering were simple.

- If you have an answer you need to raise your hand.

- If someone else is speaking you will not interrupt.

- You will not put down anyone’s ideas.

We had an interesting range of answers. My own one was that the question itself was wrong!

We then moved on to the next question. ‘Do parents behave the same with all their children? This lead us to probe: what is love? We came up with 6 definitions of love. Makrand had a very good observation: all the definitions are only expressions of love!

Padmanabh also does Philosophy for Adults exercise in corporates. This is combined with goal setting. Padmanabh told us that the answers in both the student and adult exercises are very similar. At the end of the talk I had a suggestion. I said that instead of doing these philosophy for children classes in school can we do it at home. Padmanabh’s observation was that these discussions may not be done as honestly at home as they are done in school.

Met with quite a few interesting people in the workshop –

There was Manoj Joshi from TeachForIndia. Manoj, like me, finished his engineering in 1990, from Vivekananda College, Mumbai. He spent most of his working life in IT – about half of it in the US. He was working with Cisco, Hinjewadi last. He stays in Ved Vihar society. He is currently teaching in a private school in Warje. TeachForIndia is associated with 56 schools in Pune, out of these 40 are corporation schools. 16 are private schools for lower class children. Have promised to visit his school soon. He is playing an interesting financial game with his 9th standard children – where they are given a corpus – and asked to invest in a variety of financial instruments. There is a scheme with a 24% interest rate which has created a lot of interest in students. They of course, don’t know that this guy is soon going to run away with their money J Should be fun sitting in Manoj’s class.

And then there was Makrand Bodas. He has done his Ph.D from IIT Bombay. He is Director, Geological Services for the state of Maharashtra. The Geological Survey of India is headquartered in Calcutta. I have invited Makrand to visit our school for a talk. He is Ok with a date sometime in March. A very interesting suggestion that came from him was that the next day students should meet him on Hanuman Tekdi to do a practical session on geology!

There was a team of 4 people from IIM, Pune. Investment In Man (IIM) Trust has been working for the last 44 years in the field of rural development in Pune’s Phulgaon village, forty kilometres away from Pune on Pune-Ahmednagar highway. There run an orphanage there. The website is www.iimtrust.org

Rhujuta is a person in Padmanabh’s team who looks after career counselling. I have mailed her our counseling forms. Looking forward to the stuff they use for counselling.

One was a landless farmer. He farms on his friend’s lands – who have purchased land only for investment. Most of his farms are located in the Urawade region.

Sample lesson for 8 year kids from http://www.aude-education.co.uk

‘The Donkey’s Shadow’ Teaching Notes

- Practice the exercise in focusing attention. Praise those who are obviously connected in the present moment and not day-dreaming.

- Remind children of last week’s activity and ask a pupil to describe it. Recall the purpose and any strategies used, and take further comments or evidence from children.

- Read the story ‘The Donkey’s Shadow’.

- Ask pupils to remember three things that happened in the story but in reverse chronological order. After giving time for them to do this, let them share these with a partner.

- Ask children what they thought was the theme of the story. Take answers and build up an ideas web on the board. Do not give the children them, but examples could be ‘greed’, ‘selfishness’, ‘ownership’.

- Move to using the ‘Questions for Thinking’ to stimulate dialogue.

- For a closure activity, look again at the web on the board and see which idea or ideas have been developed through the dialogue, and how they have developed.

- Discuss the ‘Thought for the Week’.

The Donkey’s Shadow

Aesop’s Fable

A traveller had a long distance to go so he hired a donkey to carry him and his bags. They set off, the traveller riding the donkey and the donkey’s owner walking alongside.

Along the dusty track they went, through the cool forest and up towards the distant hills. After a time they emerged from the cover of the forest to the bare hills where there was no shade.

It was a fine day and as time went by it grew hotter and hotter. The traveller wore a hat but still the sweat trickled down his neck and he longed for a drink. He became so hot and thirsty that soon he couldn’t stop thinking about having a drink. Oh for some lovely cool water.

‘I must rest and have some water,’ he said to the donkey owner, who was well used to walking in hot weather.

He dismounted and sat down in the donkey’s shadow, which was the only shade there was. The owner of the donkey was at ease, and sat waiting on the traveller to feel better.

Soon the donkey’s owner also began to feel too hot in the sun. He saw that the only shadow there was, was the donkey’s shadow – and there was only room for one person to rest in that shadow!

‘Move over,’ he said. ‘I own the donkey and therefore his shadow too. I want to use the shadow.’

‘But when I hired the donkey I also hired his shadow,’ said the traveller.

‘No, you did not.’ The owner gave him a little push.

‘Oh yes I did! A donkey and his shadow cannot be separated, and since I’ve paid for the donkey, I’ve paid for his shadow.’

Soon the two men were pushing and shoving each other and then thumping and punching.

While all this was going on they didn’t notice the donkey wandering away, so that when the men eventually fell exhausted to the ground there was no shadow … and no donkey either.

Questions for Thinking:

- Why did the men begin to quarrel?

- Who do you agree with – the traveller or the donkey owner? Why?

- Why did the traveller think he owned the shadow?

- What is a shadow?

- Is it possible to own a shadow? Why? Why not??

- What was the problem?

- Was there any other solution?

- How would you have acted in that situation? Why?

- Why do people share? Reasons? Evidence?

- Why do people not share? Evidence?

Thought for the Week:

During the week, see whether you share, or whether you are greedy. How do you feel at the time? What makes you share or not share?

Children as young as four are being taught philosophy in nursery, BBC Scotland has learned.

Philosophy can be described as rational investigation of existence, ethics and knowledge, experts said.

Teachers use stimuli such as a story or picture to encourage learners to think about things at a deeper level.

They ask children simple, open-ended questions such as “how do you know that? What shows that?”.

I giggle, therefore I am

Stuart Jeffries meets nine- and 10-year-olds who are learning philosophy at school

“Now make sure your feet are flat on the floor and that you’re sitting in a balanced and upright position,” says Paul Cleghorn. It’s very quiet in the 1.30pm philosophy class for nine- and 10-year-olds at Sunnyside primary school in Alloa. Cleghorn, who’s headteacher of this 500-pupil school, is trying to prepare the class for a spot of Socratic dialectical reasoning. Possibly the central heating is up higher than it was in the days of Thrasymachus and Alcibiades, and during the next hour a few slump in their seats. But not many.

“Let’s start with the sense of touch. Be aware of how your feet feel on the floor, the clothes on your skin. Look around now and notice the shapes and colours of things in the classroom. Now let your hearing go right out to the furthest sound you can hear.” Outside, the mist descends down the Ochil Hills of Clackmannanshire; inside, two boys are elbowing each other in the ribs and giggling, while the rest of the class finish the preparatory calming exercise.

This exercise was devised by Cleghorn under the influence of Lao Tzu, who, as you know, said: “Practise not-doing and everything will fall into place.” Indeed, this maxim is quoted at the start of a British Medical Journal paper, Mindfulness in Medicine and Everyday Life, published last November. Cleghorn has thoughtfully photocopied it for me, and the article does help to explain why the exercise of Mindfulness Practice – as it is known – might be useful to help children learn how to think.

“We spend much of our daily lives doing things automatically without thinking,” argues the University of Bangor’s Paul Elliston in the BMJ paper. “When we are on automatic pilot we unknowingly waste enormous amounts of energy in reacting auto matically and unconsciously to the outside world and to our own inner experiences. We are also more likely to react to situations in a ‘fight or flight’ way rather than in a more considered way.” The alternative is mindfulness, which is “about intentionally becoming aware of our bodies and minds and the world about us while, at the same time, not making judgments about whether we like or don’t like what we find.”

And it is precisely this more considered way of thinking that Cleghorn hopes to instil in his children by means of this philosophy class.

Each week the task is to think about a particular theme and discuss it in a Socratic manner, though most likely with a stronger Scottish accent than was prevalent in ancient Greece. To galvanise a discussion about fear, the children studied and discussed Kit Wright’s poem What Was It? which one girl recites:

What was it

that could make

me wake

in the middle of the night

when the light

was a long way from coming

and the humming

of the fridge was the single

tingle

of sound

all round?

Cleghorn asks the children to think about situations in which they’ve been afraid. Fresh-faced Alan pipes up: “Sometimes when you’re alone in the street where I live, you can hear nothing except a bird in a tree and it’s frightening. Until you realise it’s just a bird.” “Interesting,” says Cleghorn. “So you’re talking about an imaginary fear. We give a name to this kind of thing when you’re looking for evidence for an opinion. Perhaps you’ve come across it?” Two boys continue to elbow each other, while the rest of the class furrow their eyebrows earnestly. “No? We call it reasoning. We’re trying to look in a sensible way at the evidence – whether it supports something or not. In Alan’s case that means finding that there is no evidence to justify his fear.”

The class moves on to this week’s theme, which is service. Cleghorn reads a short story called Old Memories, specially written for him by his sister, Stephanie Baudet, the children’s fiction writer. It’s about a primary school boy who, as part of his personal and social development course, has to visit an old people’s home to talk to the residents. He really doesn’t want to go. “Stephen didn’t know any old people and hadn’t a clue what he would talk about. Anyway, some of them were a bit daft, weren’t they? Talked nonsense. It would be really boring and embarrassing.” It’s a rather didactic story that concludes with young Stephen being entranced by the old people’s stories, but it’s one that stimulates a philosophical conversation about the virtues of serving people in one’s local community.

Cleghorn is keen to promote these virtues: in a paper about teaching philosophy with children, he argues that life chances are just as affected by emotional intelligence (developing empathy, controlling emotions and being self-aware) as by IQ. He further argues that philosophy can help to develop both kinds of intelligence.

What’s most impressive about the very sophisticated discussion that follows is that the children unexpectedly leap beyond factual questions about the story and straight into philosophy. They’re getting used to thinking philosophically and expressing themselves accordingly. Heather says: “Stephen hadn’t really got good reasons for what he thought at the start of the story. Maybe he hadn’t got enough evidence.” “Good girl!” says Cleghorn. “What does it mean if you haven’t got enough evidence?” “You’ll just have prejudices.” “Very good indeed. And there is a word related to prejudice. Stereotypes. Like all French people have strings of onions around their necks or that all Scottish people play the bagpipes and wear kilts.” The last remark prompts some cross looks.

The discussion touches on philosophical questions of induction and deductive reasoning, the value or otherwise of civic virtues and, less relevantly, some trenchant thoughts on Alex McLeish’s stewardship of Rangers FC and why some girls fancied one of the members from Westlife until he changed his hair. Karl Popper would have been proud of them; Plato might have seen them as budding philosopher kings and queens. In future weeks, they are to discuss beauty, vandalism, goodness, theft, happiness, and global warming.

Cleghorn is trying to develop a community of rational inquiry in his philosophy classes. What this means practically is that children sit in a circle or at least a position where they can see each other; they listen attentively to each other, give reasons in support of their views and try to say nothing but the truth. Like Socrates, they are to be respectful of others’ opinions, but to test them through close questioning to see if views are well founded. The teacher’s role is to focus attention on important points, seek clarification, not allow the class to degenerate into conversation but to consist of dialogue, and to praise children who contribute positively.

That, at least is the theory. But it is tough in practice for the teacher, and demanding for the children. It requires high levels of attention and, more challengingly, skills in oral argument that really haven’t been taught in schools since the ancient Greeks.

Back in his office, Cleghorn is slightly disappointed. “It wasn’t as good as earlier classes I’ve taught. It’s thrilling to hear children develop rational lines of thought, to have a real dialogue with each other, and really care about what’s going on in the group.”

But what is the point of teaching philosophy to primary school children? For 2,500 years it has been thought to be too difficult and as a result has been restricted to college and university courses. Cleghorn is convinced that young children have a natural spirit of inquiry that is frustrated as they grow up. “As very young children move into the world of language they begin to ask questions about everything. They’re always asking why, why, why. Unfortunately, in most cases this natural curiosity is largely knocked out of them by being ignored or told not to ask silly questions. The philosophy programme with children seeks to restore what is in fact absolutely natural, and build on this.”

Cleghorn is part of a growing international movement. For the past three years he has been developing a “philosophy for children” course for primary schools for Clackmannanshire education authority, which now involves 30 classes and 800 pupils, some as young as eight. Cleghorn hopes to teach six-year-olds the rudiments of Socratic reasoning later this year. His is not the first school to attempt this but it is the first philosophy programme for primary school children to be adopted authority-wide.

One drawback so far is that there are no follow-up philosophy classes at secondary schools in Clackmannanshire, but Cleghorn does not think this is insuperable: “Philosophy as we teach it involves giving the children a skill in Socratic process. And that will be very useful in a range of subjects, from literature to the sciences. Thinking logically will make pupils’ later study deeper. It infuses the curriculum.”

What particularly strikes me, having attended one class, is that philosophy helps children to develop their oral articulacy – and that seems to be very important at a time when British schoolchildren are not thought to be as able at arguing as their continental counterparts. “In fact, one reason the kids like the classes so much is that they don’t have to write anything down, it’s all verbal. That said, I’ve noticed that pupils’ written work does tend to get richer once they’ve studied philosophy. But at the moment this is all fairly anecdotal.” It is likely to become more than anecdotal: psychologists from Dundee University are currently monitoring classes to find out how philosophy classes contribute to cognitive development.

Cleghorn has been influenced in his initiative by the American philosopher Matthew Lipman, who in 1969 developed a philosophy for children course in US schools. “Philosophy for children,” writes Lipman, “is actually seen as being about critical, creative and caring thinking, which is the main characteristic of democratic society.” Just as it was in ancient Athens.

But why is it important for children to have these Socratic reasoning skills? “It’s becoming more recognised how important it is to learn about learning,” says Cleghorn. “The rate of change is so fast and the volume of knowledge is ever increasing. We spend so much effort teaching children the content of subjects but don’t teach them how to think, how to learn. If we don’t teach that, there will be tragic consequences. In the next 10 to 15 years one of the effects of globalisation will be that economies will become more and more knowledge-based. If we don’t have young people who can think well, the effect will be felt across the whole country.”

Excerpted from Mar 2002 article by Stuart Jeffries in the Guardian

Children are exposed to all kind of influences. They see that women are not treated equal to men. They also observe other expressions of inequality. They have learned to think and by exposing them to an activity in which all are equal we offer them the opportunity experience equality and that is by far the best way of learning. Coming together, constructively working together, strive for success together gives a very good opportunity to develop together.

Introduction of unknown sports is easier than rebuilding the rules of existing sports. So we choose tumbling-judo as a mixed sport for smaller children (up to 7) and korfball, that has been developed to play as a mixed game, for older children.

We have observed a few games of mixed sports in the field. The results brought tears into our eyes. Boys and girls of 14 to 16 played korfball together like they had never done else. We saw boys and girls having fun. At the same time we saw that they did everything not to hurt one another and they played seriously and with respect. A mother, who was observing, clearly was enjoying what she saw. These children, we are convinced, never will think again that the different sexes originate from different planets.

Faciltator Training Program, P4C

The program was organised by Chalo Think Kare Foundation. CTK is a Section 8 company – which means it is a Not for Profit. The advantage of a Sec 8 company, vis-à-vis a trust, is that it can operate across states. CTK currently has two directors – Akshay and Padmanabh. The board of advisors include the Deshpandes, Archana, Sunil and Kishori. Most of the participants were looking at some kind of training targets. And even promotional material to help reach out to institutions. We agreed that the first priority is going to be actually conducting sessions ourselves.

The venue was quite central – Prabhat Road. The number of participants at 12 was very comfortable. I thought that we could scale up better if we have larger participant groups. In hindsight, 12 was a nice number. Could chat up with each of the participants over 3 days. Also we could give each other feedback as all of us got to present sessions. My suggestion to Padmanabh was that we could possibly reduce it to 2 days. More working professionals can do this course on Sat-Sun. For that to happen, we may need to start at 0830 hrs. Finish at 1900 hrs. If we make the course residential (One night only) – the impact will also be better.

The pace of the workshop was quite appropriate. One suggestion that I had to make was that there should be more pause points, where students can reflect on the discussions that happen. Ideally, write down what they have learnt. I did that at the end. Kaizen was to get students to share their reflections on the WhatsApp groups. The group will meet again in first week of Oct. Would be a good idea to check for implementation of action points then. In Jan 2019, Paul and Doris are going to come in from England for a week long training program – which I shall be missing because of my cycling trip – and after that we can say that the training is actually done. Am putting down my thoughts on the parts of a typical session.

Focussing: Getting students to use their senses certainly helps in calming down. In terms of sensory load, I feel that our eyes carry most of it. So closing the eyes is always a good calming-down tool. In the first session, the facilitator decided that she is going to use the story of an experience to take students through an imagined sensory perception. This template was followed by almost everyone then. I think that a simple relaxing and focussing on the present was a better approach. I tried that in my session – where I focussed only on the sense of listening – and to some extent feeling. To feel your breathing. To sense the vibrations when one chants an Om. To sense the flow of blood in the arteries and the pumping of the heart. To listen to the sound of the fan in the room, the traffic on the road. Another interesting experience was to make students realise that the breath in is cooler than the breath out. There were very few spoken instructions – allowing students to concentrate on what was around them. The ideal duration of the focussing part should be about 2 minutes.

Discuss HW: If we don’t discuss HW, no one does HW, so it is important to start the session with a discussion on the past session’s Thought for the Week. We need to ask participants to share their experiences related to the TFW. For example, if the Thought for the week has been stealing, the stimulus should be: ‘Did anyone of you end up copying someone else’s work without permission? How did you feel when you did that?’ We need to remember that this is something that we do at the start of the session, so we have to limit the discussion to simply experience sharing – and not counter questioning or theory formulations. Else we will run out of time for the basic session.

Rules of discussion: The idea of using a placard to remind students of expected behaviours is excellent. Placard examples are: Participate, Listen, Cooperate, Appreciate, Pay attention, Don’t insult. However, most facilitators (umpires) did not end up using these yellow cards too often in the game. Even for the members, trying to remember too many new rules in a game is kind of difficult. My thinking is that it is best if we restrict it to a single rule. I did that in my session – focussing just on listening. Elaborating that it meant that the student is assumed to be listening only if she is able to change her idea based on what someone else said. Or is able to develop the point started by another person. We could have similar elaborations – for example, in everyone participates, we can say that the expected behaviour is that the person to your left and right should have also spoken during the session. Most of us did not end up discussing the rule implementation at the end of the session. We can probably discuss this rule in the next session. It should be included in the Thought for the Week. Maybe the idea being that how many times in this week did you actually change your opinion based on ideas that you heard from someone else..

Story: Should be something that the audience can relate to. Fairy tales / Panchtantra tales are ideal – as they are something that go down well with both adults and children. Another advantage is that most of us have heard them before – so relating to it is easier. I have also tried in my sessions to use a reference to Hindi films – through the songs – instead of narrating the whole story. In creating original content, it is important that the author remembers to delineate the character. Most of the training program happened in Marathi. There were instances where I had to ask facilitators to translate words into English for me. I am not sure if students would do that in a class. So the better strategy is to use as simple words as possible in the story. Another thing that does not transplant well is culture. In one of the stories, the mother hugs her son. We thought that Indian culture is not one which has too much of PDA (Public Display of Affection). So when the facilitator asked, what does it mean to hug someone, there was a fair amount of silence. For an Indian child actions express love more than words. Maybe a foot massage will make a mother feel happier than a hug? When we translate Paul’s stories, we can keep these cultural issues in mind.

Activities: Are definitely more interesting than stories. In fact we can convert stories to activities – by asking students to enact the same. This has been done by a facilitator by asking students to play two goats on a narrow log across the river story. I did that with the ‘Who’s talking’ story too. Coming back to our training, we did these 4 activities: Percentage, Tower building, Saying nice things, Changing the Rules. Interestingly, all of them were done in groups. We can use random assignment techniques like chits or birthdays to assign students to groups. This has an advantage. Strangers are more likely to have different perspectives compared to friends. All activities involved moving around and talking.

The best activity was Tower building. In this one team member is blindfolded and has to be guided by her team mates to build a tower using small cardboard rolls. Time was kept and height of the tower measured. The discussion focus was on competition. We went on to define competition and ended up with HW as: Do I compete? Where? Why?

In Percentage, debating questions were given – and members were asked on a scale of 0-100 about their agreement or disagreement with the topic. The groups were then asked to arrive at a consensus. As an intermediate step, the facilitator aggregated all those who were in the same range of agreement / disagreement. We could have presentations made by each of these groups – and then debates on what percentage the agreement should be on. Two groups and two topics for discussion would be ideal. The HW given here was on emotions, whereas I felt it should have been on listening and changing.

The activity ‘Saying nice things’, was quite wonderful. What I liked was the paper folding that happened from bottom up as each participant wrote in her observation. Possibly we could look at common threads in the talk to help people identify their dominating strength. Here were the good things that my group had to say about me:

Simple Living

Takes Notes

Fearless

Different

My own comment was – good on ideas, not so much on implementation. If we were to summarize my personality into one word, then what would that be? Challenger? The advantage of this exercise would be that along with thinking, it would help each of the participants establish a sense of self-identity.

In the activity – Changing the Rules, it is best to take a single indoor game – and actually ask them to change the rules for that. Some amount of playing the game with the new rule will help make it more fun. As Padmanabh says, the first rule in our sessions should be that the participants should have fun!

Questioning: For young students, the first set of questions is always about facts related to the story. We had an interesting method where students were asked to narrate the story facts – but in reverse chronological order! The answering should always be done in groups. No matter whether a story or activity. Ideally, we should ask only one member to speak on behalf of the group. This member can change across questions. We should keep a max of two questions for discussion. One of them should end up as a Thought for the week. The facilitator should be ready with probing questions in order to stimulate thinking and fill in pauses. If the key point is about sharing, we can ask why do we share? (The why do we not share – was HW) The questions are supposed to lead a group in a particular direction, but without the group realising it. Else, the Eureka feeling will be lost. We need to have the a clear exploration area emerging from this questioning. Note, not an answer – but an exploration area.

Thought for the Week: (TFW) As Padmanabh puts it, TFW is really the crux of the whole session. If we are not able to arrive at a good Thought for the Week, the whole session has been a waste. Suggestions for the Thought for the Week are given in the manual. However, I think it is better to go with the flow – and give students some leeway in deciding what the thought for the week should be. One thing we have to keep in mind is that the Thought for the week should be something that should be able to be experienced, ideally in the timeframe of one week. In my session, it came as – What are the different ways we steal? When is it Ok to steal? When is it not Ok? At first sight, not too many of us thieves in our personal life. We may have stolen something some time in the past, but whether we are going to become kleptomaniacs this week is doubtful. However, we can extend the definition of stealing to copying – stealing IP – and we then realise that we do that more often. Here are some interesting TFW questions that we came across in our sessions:

Why is our default feedback always critical?

Do we remember criticisms more than we remember praises?

Doesn’t every negative always have a positive perspective? Frugality is the other side of the stinginess coin.

Can we change a person by speaking good of her?

What is fear? What kind of fear should society impose upon its members?

Are rules important? Should they be changed?

What do you do when you get frustrated?

Is our happiness dependent on others?

Demo session of Philosophy for Adults

Sunil is one of the advisors for the CTK board. He runs a P4A program for his team at Greeny – a company that works in the area of Solid Waste Management advisory. Greeny has a mandate from 5 local municipal bodies in Maharashtra related to spreading the message of waste segregation. Padmanabh anchored one session for the Greeny team with we guys being the observers.

We started the session with a revision of the previous TFW: If we have someone whose opinion differs from ours, do we take it into account? There was an initial silence that was broken by Akshay. Here is where I think I got a feeling that facilitation should always be pair-share. When two facilitators work together – one of them can behave as a participant and nudge the group in the desired direction. Also she can serve as a feedback mechanism for the other facilitator. Coming back to the HW, participants were specifically asked to give an example or share experiences.

This virtue of patience was discussed. Sunil himself felt that he should first listen for 30 s before responding. He has not been very successful in this – though the silver lining is that he at least let’s his team members finish their sentences before responding J One of the participants talked about an instance where one of his friends, Ranjeet, asked him for a loan. His other friend advised him not to give the loan, as Ranjeet had a chequered track record on repayments. The advice was ignored – and the loan was given. A year and a half has passed – and there has been a loss on the financial and friendship front. He was then asked by the facilitator if he would do it differently now? The entire group pitched in – and came to a conclusion that decisions taken in haste are those that we regret the most. I feel that it is best to come to some consensus when discussing previous week’s TFW. It helps give a behaviorial cue for participants. A delayed moral of the story, if you like.

Padmanabh then told the group an enchanting story about a young man who wants to cross the sea. He borrows a boat from an old man – who tells him that if he is in trouble – then all he has to do is to call out to the old man. The young man quickly jumps in and starts rowing furiously. He keeps at it all day – and when the night sets in – he gets worried. He remembers the old man’s advice and calls out to him. To his surprise, the old man’s voice replies immediately. ‘Young man, the least you could have done was to untie the rope before you started rowing.’

The class was broken into groups of 3 – and each group was asked to discuss – ‘Why do you think I told you this story? How do you relate to this story in your life? What do those things symbolize – boar, anchor, rope, ocean? What role would you like to play?’

One of the metrics used for this session was the number of questions asked by participants. One of the interesting questions raised was – Did the old man also make a mistake? During a discussion on the question – the observers felt that the facilitator had let his own bias creep into the discussion. The group came up with the key word – Janeev – which loosely translates to wisdom or insight or realisation. The TFW was: How is realisation different from experience? We ended with a vote on rule observation. Those who felt that they had observed the rule were asked to jump one step ahead. If not, jump back. You also had a choice of staying where you are.

Interesting Tidbits

Highlight of kaizens in the session was by Jayant Gadgil – who as an aside is related to the royal family of Aundh. After narrating the donkey’s shadow story – he formed three groups. Groups were tasked with renarrating the story – one from the owner’s perspective, one from the customer’s perspective and the last from the donkey’s perspective.

Arti Jadhav also had an interesting activity as part of her Helen Keller story. She asked groups to walk by closing both their eyes and ears. When you do that – you can feel the vibration in every step that you take. Btw, Helen Keller’s teacher had also been blind for some time.

In order to measure the effectiveness of the program, a Before After video of the class helps. A video needs to be taken in the first session of the class – and again the last session of the class. This serves as a very important evidence for the transformation.

As a facilitator, if you have not understood what a participant is saying, then pause and ask for a clarification.

An experiment worth trying – a P4A session on WhatsApp!

Jo Rakhto, to Rakshas. Jo Deto, to Dev.

Sadness is not the only opposite of happiness

Finally, improvement areas for yours truly – Time management and Directions discussion.