This was my first visit to Prayagraj, though I have crossed Allahabad by train on a few occasions. Was here primarily to spend time with my sensei, Prof Ashok Pratap Arora. Prof Arora has been one of the best teachers I ever had. No matter how much I try, I just cannot get his Socrates technique of questioning working in my classrooms. Witnessed the same when I was discussing a problem of increasing enrolments at our schools. The only two questions he asked me: How is your school different from others in your neighbourhood? Do the school kids’ parents know about this? Hmm.

The Student with the Sensei

I finished my work in Jammu and boarded the Udhampur Express that terminates in the Subedarganj station of Prayagraj. To decongest the main Prayagraj Junction, many trains have been diverted to smaller stations around the city. Subedarganj is one of them. Google Maps showed me that Prof Arora’s house was a 6 km walk from there. The train was late by 4 hours, and I had decided to walk a bit and then take an e-rickshaw to reach his place. Was taken aback to find Prof Arora waiting on the platform.

Prof Arora stays in an area called Kalyani Devi, which is not too far from the banks of the Yamuna. We drove to his house in the Gurugram registered Swift Dzire. The house was built by Ashok ji’s father in the fifties. His dad also grew up in Allahabad, a city that was founded by Akbar. There are two hypotheses about how the city got that name. ‘abad’ usually refers to the founder or settler. ‘Allah’ settling down at Prayagraj probably indicated the holiness of the city across faiths. The other hypothesis is that Akbar named it after his self founded religion of ‘Din-e-elahi’. In the colloquial language, you still refer to the city as Illahabad, not Allahabad.

Could see that a lot of love had gone into maintaining the house. Sir tells me that the attempt has been made to keep it the same way as was in his parent’s time. The furniture is from the sixties – and in prime shape. Each of the artefacts at home has a story behind it. There was a lovely Hanuman painting at the entrance. The painting had originally been made by a sant who founded one of the largest Hanuman mandirs in Allahabad, walking distance from the main railway station. The painting suffered some damage from termites – and Sir located an artist from Bengal to copy the painting before it rotted away. The artist has used pencil lead dust to lovely effect.

Vandana ji, Sir’s better half, was not at home. She was in a training program on drone flying. HAL has a small setup in Naini, across the Yamuna. They had advertised recently for this course. Maam has always wanted to fly planes – and she had once been rejected because she did not meet the height criterion for a glider course. So she decided that it was time to make amends. So at the young age of 64, she was busy attending classes on the theories of flight.

Drone Sighting at Sangam

Sir got into the kitchen to make some lovely cups of lemon tea. Had a quick shower before we sat down for a chat with Deepak ji, one of Sir’s friends. Deepak also grew up in Allahabad. Prashant Bhushan, one of the AAP veterans, is his senior from school. Prashant and Deepak’s elder brother studied in the same class. Prashant’s dad, Shanti Bhushan shot into the limelight in the seventies when he was the lawyer in the case filed against Indira Gandhi by Raj Narain. That was the case that led to the infamous emergence of 1976. Shanti’s career really took off after that – and he shifted base to Delhi to practise in the Supreme Court. Prashant had an interesting experience in education. He first joined IIT Madras – and quit the program after a few months. Next year he got admitted to Princeton – and had the same experience there. Finally, he came back to Allahabad to join the law program at Allahabad University.

Deepak’s life has also been quite interesting. In the nineties, Deepak ran the franchise for NIS, NIIT’s sister company that ran sales training programs. Those were the days when every city had multiple NIIT and Aptech centers. NIS had a great run as its students got lapped up by an industry that was hungry for good sales professionals. Both NIIT and NIS saw a decline when the ‘formal’ education sector recognised their success. The mushrooming of computer engineering and MBA programs saw students moving away from NIIT and NIS classrooms. One thing that NIIT /NIS could not match was the lure of the ‘degree’, which meant not only an upward career trajectory but also improved marriage prospects.

Deepak was a visiting faculty at IIM Lucknow when he was running the NIS franchise. He got invited to join ISB Hyderabad, when it was just starting off. Deepak had been running the corporate training programs for NIS – and ISB was looking for someone to help in the executive education programs that they were launching. Deepak talked of the history of ISB. Its beginnings with Rajat Gupta of McKinsey. About short lived deans from academia in the initial days. About Deepak Jain from Kellog deciding to join as dean – and then Kellog making him an offer to become their own dean. And finally getting Prof MR Rao, who had retired recently from IIM Bangalore, as dean. About Ajit Ranganekar, the capitalist son of a firebrand communist mother, who happened to be the only communist Member of Parliament that Bombay sent to Delhi.

In the meantime, Vandana ji had come back from her class. Was amazed by her energy levels. After 2 hours of driving and 8 hours of attending class, she still dished out a 7 course meal for all of us. And this was not to mention the 7 course snacks that we had as we sipped the non-vegan Chaas. By now, I had declared my Allahabad stay as vegan cheat day. So went on to gorge on Gulab jamuns and mava filled parbal ki mithai. The only thing that I managed to stay away from was the paneer. By the time we wrapped up dinner it was 2245 hrs.

One thing about the house that I liked was its 15 ft high roof. City dwelling folks, staying in rooms with ceiling heights of 9 ft, don’t realise the added comfort that the increased volume of air brings. I did not need to switch on the AC in the room as a result of that. Had a good sleep – and got up at 0530 hrs, only to find that I was the last person to wake up. We had spent the previous evening in the aangan. It used to be open to the sky in the earlier days, but Sir has got a translucent sheet installed to keep the rain out. The family is away for months – and the roof makes it easier to maintain the house. Caught up with Sir in the drawing room. Was reminded of the similarity in design of the house to my grandfather’s house in a narrow galli of Samastipur, Bihar.

Prof Arora was 5th of 6 children of his parents. The entire clan still meets once every 2-3 years – about 50 to 60 people land up in a different city for a meticulously planned 2-3 day get together. Sir has two daughters. One is a CA who stays in the US. The other is a lawyer who is based out of Gurugram. He has three grandchildren. He has just returned after spending a few months with the US daughter – and turns out the grand-daughter is following in grandfather’s footsteps. At the age of 7, she devours 200 page novels in a day’s time. She can also do two digit number multiplications in her head. She has been recently accepted in the gifted children’s program of John Hopkins University. His Indian grandchildren attend the very interesting Heritage Experiential school in Gurugram.

The discussion veered towards Ashok ji’s own childhood. In the sixties, schools would decide a student’s entry level class based on entrance interviews. When 5 year old Ashok was taken for his school interviews, the first school asked him to do some reading. The Principal asked his dad what reading material should be given. The dad suggested that the day’s newspaper would do. Ashok impressed the Principal with his reading and was offered direct admission to grade 6. His mother was of the opinion that starting at grade 6 would be too much for a 5 year old. The next school offered him admission in grade 5 – and the offer was taken up.

Ashok ji went on to Allahabad University, where he was accepted for the highest ranked BSc Physics program. He had finished that by the age of 13. By 15, he was done with his M.Sc. Physics, following the footsteps of alumni like CV Raman and Meghnad Saha. Allahabad University in those days was an IAS factory. And that was the next target. But that was the only exam that he faced so far which required a minimum age. So he ended up enrolling for the university’s MBA program. 700 people sat for the exam. There were only 15 seats. Needless to say, Ashok ji got selected. With a small class size, classes were more discussions than instructions.

By the age of 17, Ashok ji was done with his MBA and was offered the post of a lecturer at the MBA department. Around that time, there was tragedy at home. At the relatively young age of 62, his dad passed away. 5 of his elder sisters were already married. Ashok, his younger sister and mom were staying together. His dad had worked with the UP government, so financially there were not too many worries. Yet Ashok decided to take up the teaching offer. It was a Class I post – and offered the same salary as an IAS officer. During his discussion with college seniors who had joined IAS, he realised that the real bosses were still the politicians. Ashok came to realise that, unlike bureaucracy, management was more merit-centric. So the IAS idea was put on the backburner.

After a year of teaching, he realised that he needs real life experience to be more effective in the classroom. Around that time, a local Allahabad company, Geep Batteries, one of the leading torch manufacturers in those days, was just starting its Market research division. Chucking out his secure government job, Ashok decided to join them as a Management trainee. His manager had earlier worked in IMRB – and was a great boss. It was like working in a startup – and Ashok was involved in all aspects of the business: from pitching to clients to field visits and focus groups. He spent 3 years there. When he realised that his learning had stopped, he decided to sharpen his axe – and enrolled at the FPM program at IIM Ahmedabad. There were no plans to join academics, but Ashok was impressed by the open and flexible culture at the IIMs. On finishing his PhD at the age of 29, when he was offered professorship at IIM Calcutta, he took up the offer.

He got married the same year. Better half, Vandana, grew up in Bangalore. Her dad, an interesting engineer-inventor-entrepreneur, took the amazing decision to retire from his engineering business at the age of 40. He used to be a key supplier to BHEL. He then went on to start Bangalore’s first revolving restaurant before finally giving that up and moving to Pondicherry, where he spent a large part of his life. At Pondicherry he made his own caravan for his touring around. Had plans to convert his Nano to electric, but gave up on that when he could not find reliable suppliers. After Vandana’s mother passed away, her dad moved in with the daughter to Allahabad. His tinkering continued till his last days – and his best friend in Allahabad was the local electrician!

We went for an early morning walk to the Yamuna. It is about a km away. Unlike Varanasi, Prayagraj does not have too many ghats. Probably, the rivers’ meandering does not allow for the presence of permanent structures. There are two bridges that cross the Yamuna and one over the Ganga. Most of Allahabad is settled on the left bank of both the rivers. Across the Yamuna is Allahabad’s relatively small industrial area – Naini. That is also where Prayagraj Cheoki is located – another of Prayagraj’s satellite railway stations, where I had to board my train to Samastipur, Bihar that evening. The area around the ghat is famous for its clay – and so traditionally has been home to kumbhars, the pot makers. Nowadays, they are just retailers – with pots coming in all the way from Rajasthan. Another business which continues to flourish is temples. There is an ISKCON temple right next to the ghat. Unlike the metro ISKCONs, this one retains a very traditional temple feel. Ashok ji once stayed in an ISKCON temple dharamshala in Berne, Switzerland, and has become a life member of ISKCON since then.

Yamuna Ghat

The discussion turned to the choice of a retirement city. Most people who have worked in Delhi end up making that their retirement home. And in Prof Arora’s case, both his daughters were staying in Gurgaon during the time of his retirement. So why did Ashok ji choose to come back to Allahabad? The answer has something to do with philosophy. There are four stages of living: Brahmacharya, which is the state you are born in and continue to be in till the time you get married. Then you become a Grihastha. Most of us are born Brahmacharis and live our entire lives as Grihasthas. But the Grihastha is supposed to start detaching around the time the children start their own Grihastha stages. She is then supposed to be a Vanaprastha, which literally means the way of the forest. Sometimes, I look at my work with 14 Trees, an NGO in the reforestation space, and feel that my own vanaprastha ashram is going to be a 14 Trees forest.

For Prof Arora, Vanaprasthat was Allahabad – a slow process of letting go. And there is one last stage, Sannyasa, where the detachment process goes further. Sannyasa is marked by renunciation of material desires and prejudices, is represented by a state of disinterest in and detachment from material life. Sannyasa has historically been a stage of renunciation, living a peaceful and simple life. According to Prof Arora, locations don’t matter – as all these ashrams or stages are actually mental ones. I, for one, have a feeling that the stages overlap. By definition, the sannyas ashram, is the ideal one most of humanity. The planet wants us to live simple lives, because that is the only way to sustainability.

We returned back from our walk in time to see off Vandana Ma’am, who was off to our drone class. She had dished out some hot idlis with gunpowder, coconut chutney and sambar. And there was jalebi for desserts. After hogging all that and washing it down with milky chai, Sir became Krishna as he drove around his old student in the iron chariot, battling Allahabad traffic to show around the city. Our first stop was Khusro Baug, which was right next to the main railway station. Khusro was Akbar’s eldest son, and was expected to be the inheritor. But when Akbar made a decision to choose Salim over him, Khusro rebelled. He was imprisoned by his brother Khurram – and in retribution was blinded. When he died, his sister built a mausoleum for him, which is Khusro baug.

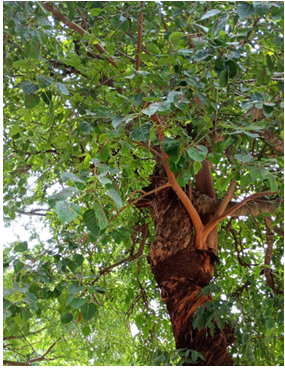

Grand Tree at Khusro Baug

Peepal Tree taking free ride

Khusro’s Tomb

We had a coffee break after this. We went across to the Indian Coffee House in Civil Lines. The establishments were started by the Coffee Board to popularise coffee drinking. Barista and CCD are proof of work well done. Like Prof Arora’s house, time has stopped at these Coffee houses. The waiters still don costumes of Air India’s erstwhile Maharajah. And the coffee does not cost a bomb, even if you sit at the place for hours. The Coffee house would make a good case study of longevity of a retail venture run by a cooperative. In most places that they have survived, low rentals must have surely helped. And possibly the seeding of the filter coffee making by specialists from Kerala and Karnataka. I had a black coffee and Sir had the normal one which seemed to be a shade lighter than the ones we get in restaurants like Pune’s Roopali.

Indian Coffee House

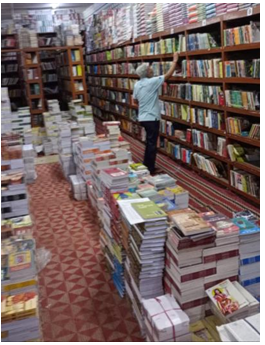

Prof Arora has a collection of a few thousand books in his library at home. Housed in his collection are the reports of about 40 students he has guided for their PhDs. Apart from the usual English fiction and management books, he also has a collection of philosophy and Hindi literature. We visited his favourite Hindi bookshop next to the Indian Coffee House. I bought a few Hindi story books for our Peepal Tree school children.

Publisher near Indian Coffee House in Civil Lines

One of the projects that he is working on is to use the vacant first floor of his house as a center for research for visiting scholars. The idea is to not make it a commercial setup – but a place where new knowledge can be created by an exchange of ideas. Professor Arora has got some expertise in data management for research – and has offered to mentor folks researchers in this area. The place has independent access – and also has a pantry. Interesting food for thought. Must send across my friend Akshay, who runs the Chalo Think Kare foundation in Pune, to visit with Prof Arora.

From there, we drove down to visit one of the landmarks which has made Allahabad Allahabad, the High Court. It is India’s biggest court – we could realise that by just looking at the roads that lead to it. Cars and bikes parked all across with a single lane left for movement. Took us 20 minutes to find some kind of parking, a km away from the court. Took an e-rickshaw to get back to court.

Sea of Vehicles at Allahabad High Court

Talking of e-rickshaws, you hardly see the old cycle rickshaw any more. I visited Samastipur in Bihar immediately after my Allahabd visit – and found the same story there. I was speaking to an e-rickshaw driver, and he tells me that he is already on his second e rickshaw. Most of them are designed to last 3-5 years. The lead acid batteries need to be changed every year, but the good news is that 99% of the lead gets recycled. Prof Arora has been very impressed by the e-rickshaw, and wonders why they have not made the transition from public to private transport. There is a huge amount of convenience attached to a 1 m wide vehicle in a city like Allahabad. Sir believes that this is a marketing problem. A question of changing customer mindsets.

In the earlier days, Sir would take visitors into the High Court without any hassles – and they could even sit and watch the proceedings in the courtroom of the Chief Justice. Today, you need permits and passes. And the security folks are so jittery, that they don’t even allow you to photograph the building from the gate!

High Court Main Building

By then, it was time for lunch. We visited El Chico, a fine dining restaurant in the Civil Lines market. It has a bakery on the ground floor, a veggie street food section on the first floor – and more elaborate Indian food on the second floor. Not being hungry we settled for a single chana bathura each. From there, we moved on to Company Garden. Started by the officials of the East India company, it is a huge place that houses the Allahabad museum, which we did not end up visiting. We did visit the Victoria memorial, which has got a pedestal minus the Victoria statue; the statue has been removed by our political patriots. Can imagine that when the current UP CM becomes PM, the old PM will get the place of honour on the pedestal 🙂

Victoria pedestal sans statue

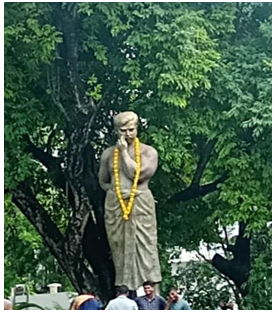

Company Bagh was also the place where one of the revolutionary freedom fighters, Chandrashekhar Azad, met his end. Chandrashekhar had gone to meet some folks at Anand Bhawan, the residence of the Nehrus in Allahabad. Nehru and Azad had very different views of how independence would be achieved. Azad felt that Azaadi could only come from the muzzle of the gun. Azad’s presence in Company Bagh was reported to the police by some members of the Nehru faction. A police posse promptly reached Company Bagh and spotted Azad under a tree. Azad was carrying a pistol – and there was an exchange of fire. Not wanting to lose his own Azaadi, Azad used his last bullet to kill himself. There is a statue of his under the tree where he shot himself.

Chandrashekhar Azad Statue

Across the road from Company Bagh is Prof Arora’s alma mater – the science faculty of the University of Allahabad. We walked in to have a dekko at the labs where Sir worked 50 years ago. And CV Raman and Meghad Saha before him. The good news is that the original equipment used by the Nobel laureate in his spectroscopy studies is still around. The bad news is that there is not too much new equipment that has been added.

Dark Room for developing photos – still in use

Modern day spectroscopy equipment

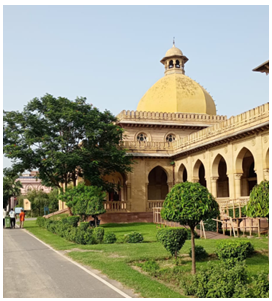

Like Pune University, they have done a good job of restoring a few buildings – alas they only can be admired from outside, as they are opened only during VIP visits.

Science Faculty Renovated Buildings

We then drove past the Arts faculty with its Senate building. The area around the university is a huge coaching hub for students keen about joining government jobs.

Coaching Industry around Allahabad University

This Hostel was an IAS producing factory in the sixties

Stopped briefly to have a dekko of Anand Bhavan, the Nehru House. Should make a longer visit there next time – having read so much about it in Nehru’s autobiography.

Anand Bhavan, the home that Jawahar Nehru Grew up in

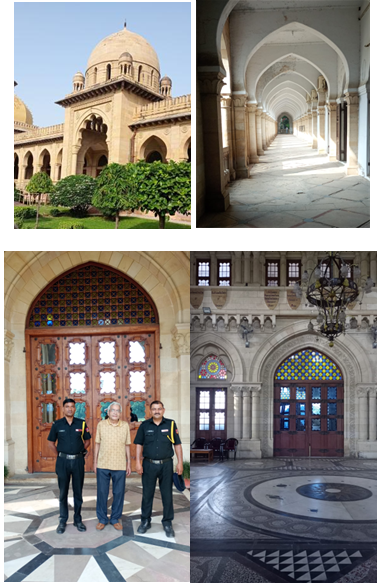

The Gondia Barauni express was running three hours late, so we had some more time before we hit the railway station. Our last port of call was the Sangam. We drove down to the river bank and were followed by an army of pandas and boatmen. Walked past the fort that Akbar built at the confluence of the rivers. Those days, rivers were the highways connecting cities – and this fort would provide a great vantage point to control trade. As with most forts, this one is also under control by the Indian Army, though there is talk of making it into a heritage hotel.

The Fort that Akbar built

Sangam – Left Bank – Main location of the Kumbh

Sangam viewed from Yamuna Right Bank

The Sangam has a famous Hanuman mandir where our friend’s moorti is in a reclining posture. It was Tuesday, a popular day for Hanuman Bhakts, so I did not end up seeing the moorti. We then drove across the new Yamuna bridge to the other side – to have a panoramic view of the entire Sangam area.

New Yamuna Bridge

This is the venue of the Kumbh, the giant religious festival which sees almost 3-5% of India’s population visit Prayagraj. The Kumbh is also a great lesson in resource management. The next one happens on Dec 24 – and I am hoping that Prof. Arora will admit me for his second class at Prayagraj then!