The biggest districts in India are the ones with the lowest populations. In J & K, an example is Ladakh and in Gujarat, it is Kutch. Both are white deserts, one a frozen one, the other a salted one. Having cycled across the frozen one in 2007, 8 years later we were on the salted one. We started from Pune on 26-Jan on the once a week Pune Bhuj Express, cycles stowed away in the luggage van. As an organizer, I felt good that most cycles escaped damage. As a participant, I felt bad that the only cycle that suffered damage was mine – the brake lever came off. Being a hydraulic brake, finding a mechanic who could set it right, even the redoubtable Bhushan, proved to be a tough task. Result – the entire trip was done with only the rear brake working. Considering that the terrain was reasonably flat, it was easier done than said.

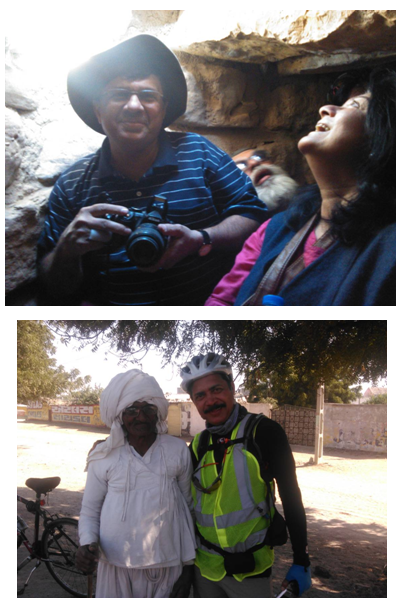

Our host in Bhuj was Darshan bhai. He treated us as if we were the Baraat party arriving on the occasion of his only daughter’s first marriage! (Am not sure if he has daughters – and if so whether married or not J) We checked into the VFM Gangaram Hotel, just a couple of km away from New Bhuj station (the old one was more in the city – and was operational till the time that the meter gauge tracks existed.) The hotel kind of shares a common wall with the palace – the Prag Mahal. Btw, the last 5 kings were all called Pragmal. A quick shower done, the team trooped into the Mahal. What was interesting about the palace was almost every room had a huge mirror angled towards the ground. Darshan bhai, being a Bhuj native, was our honorary guide – and he explained to us that the mirrors were for the king to have eyes on what was happening behind his back during his meetings at the 50 foot ceilinged Darshan hall.

More interesting than the Prag mahal is the Aina Mahal. Kutchis have been explorers and sea-farers for a long time. One of the more enterprising ones actually made Norway his home 3 centuries ago. He moved on to Belgium – and picked up the art of glass making from there. On his return to Kutch, the king asked him to make glass for the royal household. A glass factory was set up at Mandvi, the coastal sand deemed to be better for glass making than that of Bhuj. This glass was shipped across to Bhuj, a 100 km away, for use in the Aina Mahal. In the pre-elecricity era, this was the height of illumination. Diyas, glasses full of colored liquids and mirrors were placed cleverly across the room in order to create the right ambience for the king to watch the live version of Colors TV of his time. What was interesting to note is that in those times where there is light, there is heat. So the main hall has ventilators at the top and fountains at the bottom to ensure that the kingly cool is not lost.

When you get into Bhuj, any conversation with a local will inevitably veer towards 26-Jan-2002. We had landed up 13 years later, but we could still see the effects of the quake in the town. Only 6 of the 150 rooms of the place have been reconstructed after the quake. Some of it is just cracks, most of it is debris. We asked Darshan bhai how it was like to be in the quake. ‘It was like 3 Jumbo Jets making a simultaneous landing. First we thought that Pakistan must have attacked India. My grandfather was mayor of Bhuj during 1971 – and I remembered his stories. Of how he got the main masjid’s white dome painted black, so that the PAF planes could not identify the city when they dropped their illuminating flares – and how their bombs all fell in the desert outside Bhuj. (Bhuj is home to one of the biggest IAF airbases in India.)’

‘I had woken up early. A lot of relatives had come to Bhuj for a wedding. I woke up at 6 am and had gone to the house we had put them up in – to check if any of them were ready for tea. None seemed to be, so I came back. It was around 0745 hrs, I was on the top floor of our house – when the quake struck. It took me two hours to come to the ground floor. All the relatives in our guesthouse perished. The survivors were herded into the stadium. On one side, there were mass funerals, and on the other side there was the human tragedy of corpses and houses being looted. The next day the army came in – and a dusk to dawn curfew was declared to discourage the looters.’

We spoke about the earthquake with Rajeshbhai Jethia, the owner of Gangaram Hotel at Bhuj. He said that surprisingly, the only damage his 6 storey hotel building suffered was a broken water coupling. The hotel staff helped pull out 13 bodies from the rubble surrounding the hotel. A lot of survivors were accommodated in the hotel in the immediate aftermath of the quake. Because the hospital was also damaged, the Jubilee grounds of the city became a make-shift one. A cycling-gynaecologist friend in Bhuj shared that 20 deliveries a day were being done at the Jubilee grounds.

One of the buildings that saw destruction was the Swaminarayan temple. The trustees decided to build an even more grand one post the quake. It took 10 years, but it got done. The traditional benefactors of the Swaminarayan temples have been the Patels. But in this case, it was a Kutchi Muslim family from Kenya who donated the largest amount for the rebuilding. There were reportedly 15 lakh people who landed up for the inauguration. The canteen to serve them had taps through which sugarcane juice and milk flowed. And I can vouch for the hospitality of the temple management. When we reached the temple doors were closed, and Darshan bhai took us on a guided tour of the huge premises. As we were being showed one of the canteens, the manager insisted that we have to have khichdi Prasad before we leave. Added to this were bun mhaskas, the Kachchi Dabeli and the Baingan ka Bharta with bhakri, stomachs groaned at the hospitality of Bhuj.

On finishing the Prasad, we reached in time for the evening Aarti. The monk uniforms were either saffron or white. I enquired with the security guard the significance of the color. The whites were the trainees. They stay for a year or two – and decide whether they want to be monks or not. I found the whites being ragged around a bit – they all were to do a 100 Surya Namaskaars during the evening Aarti. The saffrons in contrast seemed ‘healthier’. And more self-disciplined I later found out. A saffron robed monk is not supposed to even chat with the behns. As with everything else in Gujarat, spirituality is also with a business angle. The temple serves as a kind of Rotary Club, where you can network with other businessmen. The monks facilitate deals between the co-religionists, with an implicit understanding that each party donate 10% of its profits to the temple ops fund.

Day 2, Dhordo

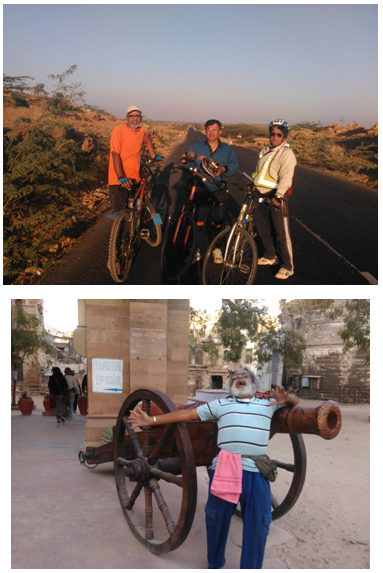

The first day of cycling. Bhuj has a set of cycling enthusiasts, most of whom are also motorcycling enthusiasts. It was fun to see the Bullet fan, who had outfitted his 1.5 lakh worth cycle with Harley Davidson style leather seats, grips and toolkit. We were escorted to the edge of town, where we started the ride to Dhordo. Dhordo is where the Rann festival is organized. Actually given the Gujju business mentality, the festival is actually on for 6 months a year. A tent city is built up, where tents are rented at 5 star hotel rates – and you pay 100 Rs to the Government do what Gandhi did free of cost at Dandi – break the salt. In hindsight, we would have been better off cycling to Mandvi, where we could have spent the evening by the beach.

But caught up in the marketing hype of the Rann Festival, we started our ride. One of Narendra’s friends had arranged for a support vehicle – a Mahindra Pickup. Munna bhai and Dipak Bhai were a great support team – and by the end of the tour – also enthusiastic cyclists! To get to Dhordo you go past the Airforce station – the boundary runs for many kilometers along the road. Looking at the angle of the afterburners of the fighter jets that flew past us, I suspect that the airfield runway is for most part below the ground as an anti bombing measure (Pakistan is less than a hundred km from here) and the jets take off at a large inclination so that they can, if necessary, avoid using the small part of the runway above the ground. You see a change in vegetation with every km that you cycle towards the Big Rann. The shrubs get sparser, the land drier. The only place where the density goes up is on river beds, which also don’t look very different from the rest of the terrain. The first major stop en route was Bhirandiyari, where you need to take a left to get to Dhordo. The toursity thing to do over there is to stop and sample the Kachchi Mawa. It is like the Belgaum Kunda. What was interesting to note that the TVs at the mithai dukans were playing Pakistani TV news channels – as the Indian denizens kept tabs on what his relatives across the border were up to – in a language which he spoke at home. A few more km of cycling and we stopped for lunch at Mehfil-e-Rann resort at Hodka. The closer you get to Dhordo, the lower value you get for your money. The resort charged us a bomb for our lunches – but on the brighter side, he allowed us to take a long post lunch nap. We peeped into his Bungas – the earthquake proof round mud huts. They were the 4 star versions – and cost 4 k per night. Interestingly, we saw round huts even in the excavations of Dholavira – so the ancestors of modern day Kutchis had realized the best architecture for safety thousands of years ago. What a pity, the modern city does not have a single round building. Although one interesting modern practice that we heard off was that of a few Rabaris – who build their houses without roofs!

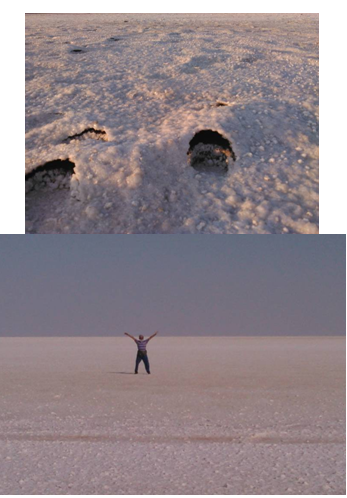

Refreshed with the naps, we reached Dhordo – only to realize it that the White salt desert is still 5 km away. We cycled past the tent city and the mela put up by the Rann Festival organizers. 80 km of cycling done by then, Mehendale kaka exclaimed in Marathi – ‘Arre aata tar mee mela.’ (Translation: I am dead now) To which the security guard helpfully pointed out the direction of the ‘mela’. We spent some time at the exhibition put up by the BSF checkpost. Jhoonta Singh, our BSF curator, was impressed enough with the high caliber questions of Bhushan, to check out whether he is a retired General. Crossing the checkpost, we were finally in the Big Rann, The salt desert loomed in front of us. Just to be sure, I also tasted a bit of the stuff that our sandals were stomping – yes the same Tata ka namak. (my first job was with Tata motors – so I can truly claim ki maina Tata ka hi namak khaya hain).

There was a troupe of singers who were attired in the center-cut Sindhi topis. (Tried my best to get my hands on one, but with no success.) The crowd watching them really got foot tapping when they started singing the only Sindhi song that the average desi can identify with – ‘Dama dam mast kalandar.’ We moved out once the song got over – and went over to the less crowded part, in order to conduct our scientific experiments. The depth of the salt varies from 5 mm to 50 mm, depending on the lay of the land. The sea comes into the Rann in the monsoon – and retreats, leaving behind its salt – and the thriving Kutch chemical industry based on salt. What happens when the water recedes is interesting. The salt forms an impervious layer which does not allow the moisture from the ground below to escape – as the summer heat builds up. The steam bumps up the salt layer – and cracks it up to escape. As you walk over the salt, you can crunch these bumps – and add to the exercise.

Experiments done we settled down to watch the sun go down. Armed with nothing more than a cell phone camera, it was difficult to capture the hues of the light at the desert sunset. One thing which the phone camera did manage to capture was the clear horizon – and the half circle of the sun. Most places with higher levels of pollution give the effect of the sun generally hazing out. Not so at Dhordo! We then beat it back to Gangaram Hotel – with the bikes in the support vehicle and the cyclists occupying a spacious Toofan, a popular vehicle in Kutch, built by the Pune headquartered Force Motors.

Day 3, Rapar

Was a pure commuting day. We had to cover 120 km, so we started at 7. As you move away from Bhuj towards Gandhidham, the industry density picks up. A few km out of Bhuj we encountered the Suzlon factory. They make the windmill blades here. We got chatting with a few employees who were outside the gate to find out what goes into the making of a blade. There are about 100 employees in the factory – and the installed capacity is only 1 blade per shift. Probably because there is only 1 mould that they have to get the fiberglass in place. We discussed the blade cracking problem that Suzlon was facing – and we were assured that none of those blades came from the Bhuj factory. Each of the blade weighs 10 tons! Interestingly, we were told that the blade length is between 46 to 48 m. Given the fact that Suzlon manufactures windmills with power ratings from 0.5 to 1.5 MW, I thought that the variation in length should be more than that.

A few km ahead was the AMW factory. A truck maker, indirectly owned by the Essar group. The factory did not seem to be as big as Tata Motors, where I have worked. I think most of their trucks are in the tippers segment. There did not seem to be too many vendor factories close by – probably because the company is mostly an aggregator – buys aggregates rather than components.

One of the things that starts giving you trouble on day 2 is back pain. This time I did some experiments and was able to arrive at a formula to reduce the pain. There are 3 ingredients to the formula. One is posture. This is what I had discovered in the Hyderabad-Vizag cycling trip. You need to ride with the seat saddle a little bit lower than normal, so that the back does not get stretched. Two is cadence. If you keep the pedaling rpm more than 65, then the strain on the thigh and calf muscles reduce, and correspondingly also the back. Three is back strengthening exercises. Surya Namaaskars every morning are a good beginning. But something more needs to be discovered. Will hope to do that by the time the next trip happens.

I gave up drinking tea a year ago, but most of the team had not. One of the duties assigned to me was to recce the road ahead and locate suitably spaced out tea shops. I must say I floundered on one occasion. We had decided to stop for breakfast in a village around 20 km from Bhuj. Dipak bhai of our support vehicle overshot the village without realizing it. I overshot Dipak bhai and ended up 5 km ahead at the Alla Rakha dhaba, which had been recommended highly for its tea by a security watchman who I had been chatting with along the way. In fact the strategy of identifying dhabas / restaurants by enquring with 2/3 locals is something which has rarely failed me so far. Having realized that the distance is too high, I called back for people to stop wherever they were, and eat whatever they could find. Waiting for the group to collect back, I ended up sampling the chai at Allah Rakha. The tea culture in that region of Gujarat involves drinking out of saucers. I think it has something to do with the business driven efficiency of the Kutchi spirit. The tea cools fast in a saucer, so you had better drink it fast – and be on your way. Not the Puneri katta where you can spend hours drinking tea.

Our original plan had been to cycle to Rapar – and then drive down to Dholavira from there. What was happening everyday was that by 1100 hrs headwinds would start. The math of the headwind is simple – Out of 360 degrees of direction, 270 degrees is counted as headwind – as it does not help the cyclist. So as a thumbrule, any wind is bad. As a result, by lunch time we had done just 70 km. Some of the locals had told me of a shortcut from a place called Ramvav. I decided to cycle ahead to check that option out. A few km out of Kharoi, one of the towns on the way – the cycle pedal fell off. Fortunately the pedal shaft decided not to fall off. With the support vehicle too far behind – and the next mechanic 30 km away in Rapar – I decided to brazen it out. Reached Ramvav – and found out that the shortcut reduced the Dholavira distance only by 10 km, 100 km instead of 110. Also the road was in not too good a condition. A Toofan was available, which would take us to Dholavira. The group in its wisdom decided that doing another 100 km journey after 120 km of cycling was not too great an idea. Plan was changed – and it was decided that we do a night halt at Rapar. Suvidha Guest House, as per plan our host for the next day at Rapar, was contacted – and it was confirmed that rooms were available. We reached Rapar just as it was getting dark. Had switched over to Anita’s cycle – so the cycling from Ramvav to Rapar was a pleasure.

One of the social themes of the trip was the ‘Bharat Swachhata Abhiyan’ – the cleanliness campaign. We had got 1000 visiting cards printed with this theme. And we talked about this at all the chai shops that we stopped at. And gave them off after cleaning up the surroundings near the chai shops. I was apprehensive that we could add to the litter if people threw away the cards. But except for one motorcycle bound student in Ahmedabad, who took the card to immediately throw it away a few seconds later, we found that people kept it with them – even though the cards were in English (should have done it in Gujarati – but my MS Word does not have Gujju fonts!) I got carried away by the cleanliness theme – and to the chagrin of my group – started demanding cleanliness even in the plates that people eat out of. Having rightly been declared Hitler-like or Modi-like in my behavior, I changed my strategy, by nudging people into the finish-off-everything-on-your-plate behavior by under-ordering. Lunch was mostly a Gujarati Thali – split between two people! Cannot comment too much on the happiness of the team as a result of all this stinginess – but am proud to report that the expenditure on food and stay per person on this 8 day trip was only Rs. 4500!

Day 4, Dholavira

We woke up in the morning, surprisingly, to meet a couple from Pune. Hubby was in manufacturing at GE and wifey was at Wipro. They had landed up late night from Ahmedabad – and came in to find that all the rooms of Rapar were occupied. They agreed to spend the night in the dormitory – and being gracious fellow Puneri’s we offered them the use of our bathrooms in the morning. With the Sadashiv Pethi thoughts of asking them to drop two of our team members to Dholavira in their hired car.

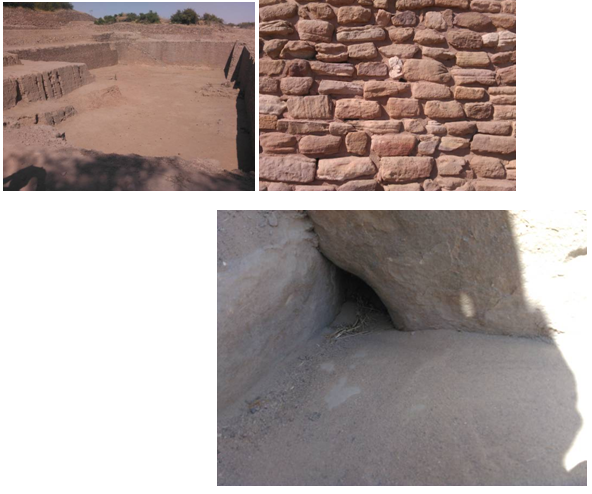

The original plan was to use the support vehicle – the Mahindra pickup to make the trip to Dholavira. It is about 85 km away – and 170 km of cycling with sight seeing thrown in was ruled out. However the group felt that we could afford the luxury of another Toofan. Took some time, but by 8 am, a Toofan had been arranged – and we did not require help from our friends, the Pune couple. We made a leisurely trip – stopping along the way to admire the Neelgai. After Balasar, the road travels for about 10 km through the Rann. This was even more of a sight than the small stretch of white desert that we saw in Dhordo. Realized the wisdom in Bhushan’s advice when he had suggested that we avoid Dhordo. Stopping for photography sessions in between, we reached Dholavira around 11.

Dholavira is a Harappan site, which was discovered about 20 odd years ago. Like Mohenjodaro (The mound of the dead), this one was also a hill. Our local guide was a runner for Dr. Bisht, who led the archaeological team which excavated the site. Our guide remembers grazing goats on the site when he was a young man. And they would find some interesting objects over there. One of those pottery artifacts made its way to Bhuj, where the museum director passed it on to Baroda, where Dr Bisht was located. He then decided to come down to Dholavira and the excavations started after that. The question that comes to mind is that why do these sites generally get transformed to hills. My hypothesis – is water. The current site of Dholavira was in the basin of the Indus 3 millenia ago. As the river changed its course, water became a bigger and bigger issue. In fact the site has two distinct levels, the lower one is the early Harappan – and the upper one is the late Harappan. The only distinct feature of the late Harappan site is the water reservoirs. So the city tried its best to continue its existence even in later millennia, by building a large number of water tanks – but given the very low rainfall – and the many drought years, the residents gave up. As the area underwent desertification, the buildings were gradually submerged under the dust that blew on – forming the mounds that are present even today.

Unfortunately the museum at Dholavira has its weekly off on Friday, the day we were there. All ASI museums are closed on Friday – we need to keep that in mind for planning subsequent trips. So we could not check out too much – although we managed to find some pottery shards and mud bangle pieces lying around on the site. We had lunch at the privately run Dholavira Tourism Resort, half a km away from the site. Met Jilubhai, the owner, and apologized to him for the last minute change in plans. (We had not paid an advance at any of the hotels that we stayed in – the advantage of traveling in off season). Post lunch we headed to Fossil Park, which was about 10 km away. The road was mostly kachcha. We kept on seeing boards enroute with BOP written on them. Realised that it stands for Border Out Post of the BSF. Although the Pakistan border is many km away, the posts have to be on relatively high lying land. The Rann not only floods in monsoon, but is also an unforgiving terrain. One thing that characterisises the Rann is the lack of ants. In the absence of these scavengers, you find that creatures that die fossilize fairly easily. We came across dead lizards and grasshoppers – amazingly preserved. The fossil park has some pretty old samples. The guard told us that the oldest tree trunk sample is 3 million and 5 years old. When asked how did he arrive at such precise estimates, he mentioned that it was 3 million years old, 5 years ago, when he had joined!

Going back to the BSF outpost, a typical one has a strength of about 20 personnel. Water comes by tanker. Electricity by either solar panels or generators. Beyond 100 m of the beginning of the Rann is no-man zone. Of course, our smuggler friends are now smart enough to ensure that only their merchandise-laden unmanned camels go into the no-man zone. There is a beautiful hillock in the middle of the Rann about 6 km from the fossil park. As with any hillock, you cannot find one in India which does not have a temple on it. This one also has one – but to make matters easier for the pilgrims, there is a subsidiary temple on the mainland.

We returned back with a saucer chai break at Balasar. How many people can you fit onto a Mahindra jeep? At Balasar, found one with about 10 people perched on the roof . I imagine double the number occupying the space below. So my guess is about 30. I am waiting for readers to disprove my hypothesis. Another interesting Gujarati innovation is the Jugaad. A mongrel made using a handcart, a diesel irrigation engine, a Bullet petrol tank and a Bullet front fork. A very functional vehicle – which can take 20 people – and return an average of 35 km per liter. A very interesting kaizen that I saw on the Jugaad is that all of them nowadays have a frame behind the driver – vehicle designers can call it a roll over bar. With a relatively high Center of Gravity, the jugaads can and do topple over. In fact Munnai bhai of our support vehicle, had a brother who dies in such an accident on a jugaad. The frame ensures that the driver and occupants are not crushed under the jugaad in such a case.

A few more wildlife sightings, black peacocks included, and a Toofan puncture later, we were back in Rapar. Made a quick trip to a cycle shop – where we managed to fit Desi pedals on my cycle – and also repair the front wheel puncture that had happened overnight. Dinner was at the excellent Mehta Bhojnalaya at Rapar. Unlimited Thali – 5 glasses of Chhaj and zero wastage, The Swachta Abhiyan was working out after all.

Day 5, Adesar

The plan was to cycle to Adesar, check out the Wild Ass sanctuary there – and then continue cyling to Radhanpur – along the boundary of the little Rann. The road to Adesar was good – traffic was not too high, road surface was not too bad. We needed to hire a local guide / jeep at Adesar in order to enter the little Rann. Of the 4-5 jeep wallahs on the stand, most of them were quite ignorant. One of them had been pestering us for the last 5 km to take his jeep – but he seemed to be a bit dubious character – and was shooed away. We managed to find Siddiq bhai – an ex Forest guard who now drove his own jeep. He took us on with the usual disclaimer – I can take you there – but ass sightings are not a guarantee. Smart guy – he did what any good businessman would do – underpromise and overdeliver. Within 45 minutes into the ride we had our Gadhkar (local lingo for the wild ass) sighting. The group was about half a km from the dirt road we were on. We tried to walk up-wind and managed to reach almost within 50 meters of the group. That is when they decided to trot away. Followed them for about half a km further into the Rann before letting them be.

Returned back from there after detouring to a salt mine. It was more a store than a mine – a dump for about 10 rake loads worth of salt. The adventure there was in being able to climb the dump whose side angles were close to 30 degrees. Dipak bhai and self decided to complete the remaining jeep ride authentic Gujju rural style – by going upper class – and riding on the roof. Realised very soon how bad it is for the aerodynamics of the vehicle.

By the time we reached Adesar it was time for lunch. At Adesar, the Rapar road meets the Gandhidham Udaipur 4 lane road. The local suggestion was to have lunch on a dhaba which was almost at the intersection point of these two roads, which serves an impeccable jawari bhakri. We found two dhabas on the intersection point – the team could not agree on which one was the recommended one. So it split – the guys who went for the better ambience of Gokul dhaba realized later that they missed out on the Bhakri. The charpoi dwellers of the more rustic dhaba were treated to a sumptuous meal – washed down with a jugful of Chhaj – something we had come to expect as our birthright now at every meal.

The good thing about the 4 lane was the road surface and the white lines to mark the edges of the main lanes. The paint used to mark the white lines has ground glass in it – so that it reflects light at night. One of the experiments I did was to ride on the white line – requires a lot of concentration – and I started hypothesizing – does it really reduce friction. Glass should be an easier surface to ride on. And my pedaling legs would notice a difference in effort when on the white strip. Got some other of our team mates to try this, and they too felt that it did reduce effort. Must pass on this tip, to my friends with road bikes, who are looking at squeezing incremental kmphs out of their bikes..

After the meal, we did a reality check. Our night halt was to be a Jain dharamshala at Radhanpur – which was still about 80 km away. The overall thinking seemed to be that we need to tone down our cycling ambitions to something closer to 60 km of post lunch cycling – there was a place called Varahi which fitted the bill. What heartened us further was the presence of a fair number of motels on the way. Along with Milind, yours truly was again made part of the advance recce party whose job was to identify a suitable hotel at Varahi. At 6 pm, we crossed the toll plaza at Varahi where there were a couple of hotels. Eager to put in a few more km under our belts, we moved towards the main town of Varahi – only to find a complete drought of hotels there. By the time we realized this our main party had already crossed the toll plaza. Took a decision to get as many people to pack up as possible – and sit with their cycles in the support vehicle. That still left 5 of us who had to then cycle to Radhanpur – 18 km away in failing light. The advance party managed the sprint quite well, reaching at 1900 hrs thanks to Milind and the presence of a service road. On reaching Radhanpur we managed to locate the Jain dharamshala – inside the narrow lanes of the old town.

There were only 4 first floor rooms available – so we hired an additional 10 room dormitory. Radhanpur was suffering from a water shortage – and the dharamshala had just run out of water. Cajoled the authorities there into ordering for a tanker of water. Although there was solar heated water available, you had to go to the ground floor tap in order to get there. The rooms were spacious – and one interesting kaizen to conserve water was that all the taps in the room were push type. So you actually needed to meditate for 10 minutes in the bathroom to fill a bucket of water. Another thing was that all taps had cloth filters attached to them – in order to ensure that we did not accidentally harm any germs that would have come in the water supply.

The main team took 45 minutes more to catch up. They discovered a hotel on the highway, but by that time the advance to the dharamshala had already been paid. On their discovering the dharamshala and the water problems therein, I realized that my popularity ratings, which had never been too high, had fallen further to a new nadir. The only small consolation was that all the loos were western ones – and considering that the average age of the group was 58, this was a big plus factor. One more curious thing about the dharamshala was that the canteen served dinner at 5 pm. So we had no option but to go out for dinner. Our main team had found a good Samaritan at the beginning of town who escorted the team to the dharamshala. Unfortunately for us, Medekar saab had a fall near the dharamshala because of a missing stone over a drain which crossed the road. He decided to stay back in the dharamshala. Our good Samaritan landed up again and decided to escort us to the best place in town for dinner. It was back on the highway, so we trooped into the support vehicle and went out for dinner in style. Post dinner we were treated to ice-cream at the famous Patel ice cream parlor of Radhanpur. We met Mr Patel over there – who shared with us with great pride, that all the ice creams we were eating were ISO certified. Which means we had an assured protein content in them, even if it meant adding some extra milk powder to the cream to do that. Must say that the serving style was unique – with my mango ice cream basically a vanilla with mango syrup sloshed over it and topped with a sprinkling of colored sugar sevai. A fitting end to a long and arduous day of cycling and adventure.

Day 6, Viramgam

The good Samaritan was back in the morning to escort us on our ride to Viramgam. He treated the group to chai and biscuits as we left. I realized that my cycle had again sprung a puncture overnight. Blast. Fortunately we were still in town, and was sure we would be able to find a repair wallah. The problem was waiting for the cycle shops to open. Bhushan volunteered to repair the puncture – and it was decided that the rest of the group would start so that cycling time was not lost. A quick repair job done, we realized that mine was not the lone punctured cycle, Bhushan’s own cycle was punctured, and that too both the tyres. Both the cycles had been parked with the support of the wall – and we suspected that there must have been some thorny stuff there. Another half an hour of repair work later, we were ready to hit the road.

By this time the dharamshala canteen was open, so it was decided that we might as well enjoy a Jain breakfast before leaving. So 4 of us, our two support vehicle friends, Bhushan and me, sat down to a breakfast of khakra, poha and chai. The chai was served in a katori this time. When I refused the chai, our hosts insisted that I should have milk instead. So my lactose intolerance protests ignored, I had a katori of milk after many years. The khakras were sprinkled with a liberal dose of desi ghee – and it was the first time in the trip that we were having poha. Breakfast done, we decided that it was easier to hitch a ride in the support vehicle to catch up with the rest of the group, which I reckoned would be about 15 km ahead of us.

The ride to Viramgam was uneventful. Roads were two lane – but surface quality was good. Lunch required some interesting decision making. Two restaurants were located at a crossroad, both looking okay in terms of ambience. What clinched the deal was that one guy’s thali provided two bhakris, one more than his competitor. That made it easier for us to split it between two people.

Our Radhanpur experience had made us imagine collectively that even our Viramgam hotel would be in the city. Viramgam is an important junction in Gujarat – with a lot of container traffic – coming in from Gandhidham and Mundra. In fact it was interesting to note that some of the container trains are loaded double decks – with two containers, loaded one above the other. It is said that you cannot enter Viramgam, from any direction, without crossing at least one level crossing. We entered the town – only to discover that the hotel we were booked in – was actually on the bypass. Every sub-group discovered new ways to reach the hotel, but before sun-down all of us were in. Compared to the austerity of Radhanpur, the Viramgam hotel was 5 star. Being a Sunday, the hotel restaurant was fully packed for the dinner crowd, so everybody ordered dinner in their rooms.

Day 7 and 8, Ahmedabad

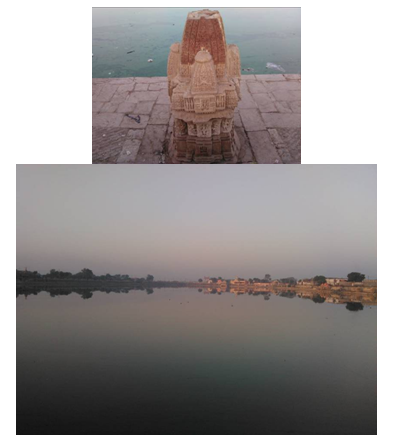

When you are in cost cutting mode, ordering room service is not a great idea. Especially when you discover that all the drinking water supplied by the hotel is of the mineral variety. Nevertheless we were nearing the end of the trip – and the budget seemed to be under control. So an ordinary, but expensive, breakfast later, we were on our last leg (and our last legs). Worth mentioning is a small excursion that we made to Mansar, a lake in Viramgam, which has 360 ancient temples built around it. I wonder what is kept away by a temple a day, but on Milind’s wonderful advice we decided to pay a pre-breakfast visit to this place. The temples all seemed factory manufactured, in the sense that most of them were identical. Unfortunately for the city of Viramgam, the swatchta around the temples was lacking – probably as a result of a jurisdiction dispute between the municipality and the Archaeological Survey of India.

We finally managed a 0830 hrs departure – and very soon came across a crossroad and a dilemma, who do we follow – Milind’s Google maps or expert advise of the local as to what is the shortest route to Ahmedabad. We decided that the desi advice would work better – a few km of riding later we were on to yet another level crossing – and then joined the main Ahmedabad – Dhrangadhra 4 lane highway. First major halt on the highway was 10 km before Sanand, the site of the Tata Nano factory. Drinking chai, we witnessed some amazing murmurations by thousands of ducks in the sky.

The next halt was for lunch at Sarkhej – at the luxurious Hotel Safar. Post lunch, a small diversion was made to the newspaper offices of Divya Bhaskar, where Narendra and Anita were duly photographed and interviewed. Ahmedabad signals are a Puneri delight – no one follows them. The thumbrule, followed even by policewallahs, is that you stop at a signal if and only if when you have at least three traffic cops stationed at the signal. The other thumbrule is that whatever Modi does has to be copied asap by all the bhais. So if there are a lot of Scorpios on the roads and everyone is running after hair transplants, you can see the Modi factor at work. Reached our final destination of Law Garden, Navrangpura, where Darshan bhai’s legendary hospitality and the rooms of hotel LA365 awaited us.

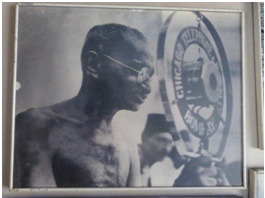

Next day’s tourism started with the Bapu ashram. Most of it is quite mundane stuff – photographs of MKG in every conceivable activity. One interesting part of the Sabarmati ashram visit was a lady who was spinning a charkha. Her demo of spinning yarn out of cotton was very cool. I think the real essence of the ashram visit should be for people to come in with cotton and go out with a dress that they themselves have woven. Maybe I need to start a Bapu-tourism circuit with such stuff. We can start this in our own school!

Another interesting experiences at Ahmedabad was experiencing the BRTS to travel to Iscon to eat their amazing puri–thali. Unlike Pune, where our BRTS is a sham, the Ahmedabad experience is the real stuff. Safety features like automatic door closing at bus stops, Announcements of time remaining for arrival of next bus – aka Mumbai local trains, centralized ticketing – and air conditioned buses – Man, this is life for a public transport junkie like me.

A good idea would be to rotate the position of trip organizers – so that people can empathize with the uncertainties and decision making required during the planning and execution. Another idea worth exploring is to keep the organization limited to cycle transport, support vehicle and stay. All other expenditure to be borne individually. An army marches on its stomach and so does a cyclist ride. She tends to be finicky about her food. Let her choose whatever food she wants – instead of regimenting the ration.

A farewell dinner was organized by Darshan bhai at Honest Pav bhaji – a hot chain of restaurants. We reached Kalupur railway station an hour before the departure of our Pune Duronto. The cycles had been booked into a parcel van of a contractor. The train departure was at 2230 hrs. The cycles got loaded in only at 2225. We were finally headed back home!

The Team