It all started with a Hanuman Tekdi walk. My aziz dost, Meher Gadekar, had joined the MS Swaminathan foundation – and has been posted in Jeypore, a taluka town of Koraput district in Odisha. I had missed visiting Meher in Ambikapur, the Chhatisgarh town where he had been working earlier. I decided to make amends this time. Now that the nest is empty, the better half was also interested. So we decided to spend a week with Meher.

I like walking to the railway station – especially so when we start a long journey. You are going to be spending 24 hours with little physical exercise – so best to flex the leg muscles a bit. Am happy to report that we encountered 5 traffic jams enroute, the first 3 were crossed on foot. Note to self: Next time there is an evening train to catch, prefer walking to the Garware college metro station and catching the direct metro to the railway station.

We got some good ball bearings gyan from Akhil, a young engineer who was travelling with us. He was on his way back to Vizag from Goa – where the company had its annual sales meet, with distributors and sales reps. He works with Schaffler – and was earlier with SKF. His job is to do vibration analysis of bearings for predictive maintenance applications. He was doing the same job at SKF. The idea is to analyse vibration patterns and then try to understand system level problems. We discussed how having motor current data would help in the analysis.

The train reached Vizag in time –we had been advised by Akhil to check INS Kurusera, the naval submarine which has been berthed, post its retirement, on Ramakrishna beach. The better half was hungry – so she got snacking on banana pakodas at the railway station. We had been advised to take bus no. 10 or 28 to get to RK beach from the station. Yours truly got into the bus – assuming that the better half would follow. But she was busy getting change from the pakoda vendor. The bus left without the missus.

No worries, thought yours truly – she will catch the next bus and come. Decided to call her– and realised that the missus’ phone was in a bag that I was ferrying. Our train friend Akhil turned out to be the good Samaritan of the day. He not only called me to inform that the missus was on the way – he actually came in the same bus to drop her off to the beach – ensuring that there was a very filmy reunion on the beach. Praise be the lord for the Akhils of the world!

We had to walk a km to get to INS Kurusera. Some of the walk was on the beach, but then we realised that sand slows you down, more so when you are carrying your backpacks. So we switched to the road, midway through the walk. We had been inside a sub earlier – at the Mumbai naval dockyard, courtesy my brother in law, who was working with the Indian Navy those days. But this was a nice revision class. The Kurusera was built in Russia in 1969, making it as old as me – though it retired from service a little bit before I did.

The sub has space for 22 torpedos. They are launched from tubes, which are fitted both at the front and the back of the sub. When you see a sub out of the water, you can see how similar its navigation is to that of an airplane. There was a big rudder at the rear, with stabilisers on either side. Unlike a plane, it had two propellers, one behind the other. The insides were, as expected, quite cramped. I assume the wiring harnesses would contribute to 10% of the sub’s weight. The sub is run by two diesel engines – which are used to charge the batteries. Come to think of it – subs were the first series hybrid vehicles used by us. Or maybe not – wonder whether the props are powered directly by the engines when the sub surfaces!

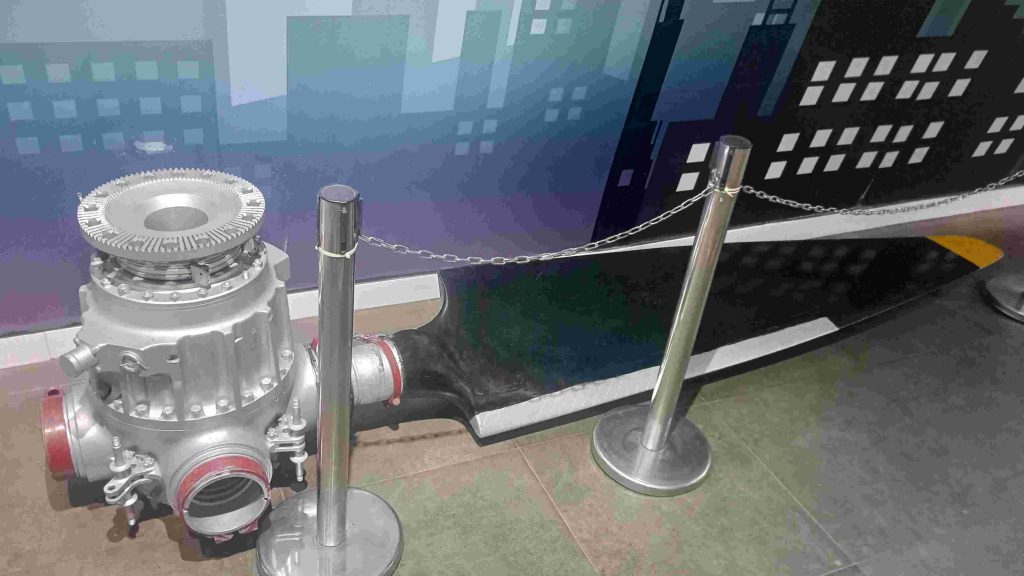

There are some quaint component displays outside the sub. I didn’t realise that the torpedos will require air for launches – combustion does require oxygen. There are more than a dozen high pressure air bottles that go into a sub. Unlike ships which don’t have to change altitudes except with the tides, subs have to worry about the z axis. To go down is simple – you just fill the ballast tanks with sea water, but coming up will probably require air from these bottles.

We then walked across the road to admire another Russian piece of equipment – the anti-sub Tupolev 76 aircraft. Russians really honor their designers – both Tupolev and Sukhoi were heads of aircraft design bureaus, with Sukhoi actually being mentored by Tupolev. The Tupolev 76 is a turbo prop – and retains the record for almost hitting 1 mach speed, even with a prop design. Like the sub, each of the 4 engines has 2 propellers – spinning in opposite directions. This makes the plane noisy, but helps improve efficiency. The plane has a range of 13,000 km – amazing , considering its size. It was also used as a bomber – and during the days when atom bombs were actually tested on surface – the Tupolev was used to drop a mother of all bombs. The mushroom cloud from that explosion reached an altitude of 56 km!

Our train to Jagdalpur was at night – and we had time to kill. So we walked back to the railway station. Walking is the best way to see a place – and I could imagine Bill Bryson – writing about Vizag. Half of what Bill bhai writes is food. I tried emulating Bill for the rest of the trip. We were tempted to sample street food – but the problem was roadside seating. So we stopped at the Andhra equivalent of a Pune khanaval – to sample the local cuisine. It was less spicy than I had thought it would be. The missus had a ragi dosa – which was quite like what one gets at Hotel Roopali. We continued our walk and had some savouries in a local market. One was a bit like malpua – the other like a gulab jamun without the syrup.

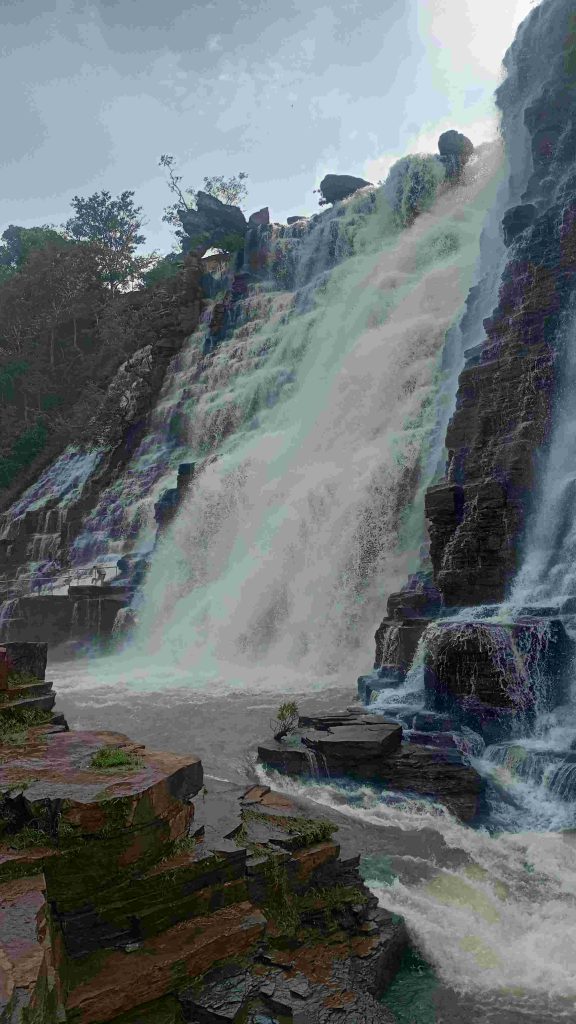

We reached Jagdalpur at 0430 hrs and checked into a hotel. A short nap later, we walked down to a chai tapri near the bus stand for the morning cuppa. Our friend made some amazing milky tea and introduced us to Rohit, a local cab owner, who asked for a very reasonable 3 K for the day’s waterfall sightseeing. Chitrakote is about 40 km from Jagdalpur. There is a more famous Chitrakoot in MP, which is where Ram and Sita stayed in their vanvaas. The approach to the falls is quite unspectacular. Jagdalpur is a plateau which, unlike the Deccan plateau, is made primarily of sedimentary rocks. The falls are created when the Indravati river leaves the plateau and erodes these sedimentary rocks. It is not too wide a river, about 300 m, but the fun is because the 300 m all falls down together. It had been raining well for the last few days and water was gushing down in 200 m of the 300 m. The speed of the water at the centre being the highest, the erosion is also the highest, giving it a horse-shoe shape. There is a small lake at the bottom and the gradient continues after the fall, albeit at a smaller slope. White waters indicate continued erosion.

Thankfully most tourists don’t venture beyond the top of the falls, even though there are steps to the bottom. The perspective changes at the base of the fall. Seeing 300 tons a second of water fall is to experience nature at its raw best. Imagine the immense energy that would be required to pump that volume upstream, even if it is just 30 m of elevation gain. One is enveloped by a mist and a sense of vulnerability. One wonders what would happen if there were to be a cloudburst upstream. The rags and plastic hanging on tree branches 6 feet above you tell you that water levels do change drastically.

Next on agenda were the Tirathgarh waterfalls, 60 km from Chitrakote. We stopped for chai at a sweetshop on the way, courtesy Rohit’s recommendation. Lal chai is popular in these parts; our tribal friends are not big fans of milk. We reached Tirathgarh around 1330 hours. Rohit recommended Maa Daya dhaba with its stone slab tables and benches. Rice, dal, papad, barbati sabzi and tomato chutney made for a homely menu. Recipes of the tomato chutney, popular in Chhattisgarh, vary quite a bit. The tribal version is raw, you basically dump tomato, ginger, green chilly and coriander into a mixer. In the urban version, onion gets added and you end up cooking it a bit. Missed sampling the chinti chutney, made by grinding red ants that live near mango trees. Tribals believe that if you consume this chutney, you will never get fever.

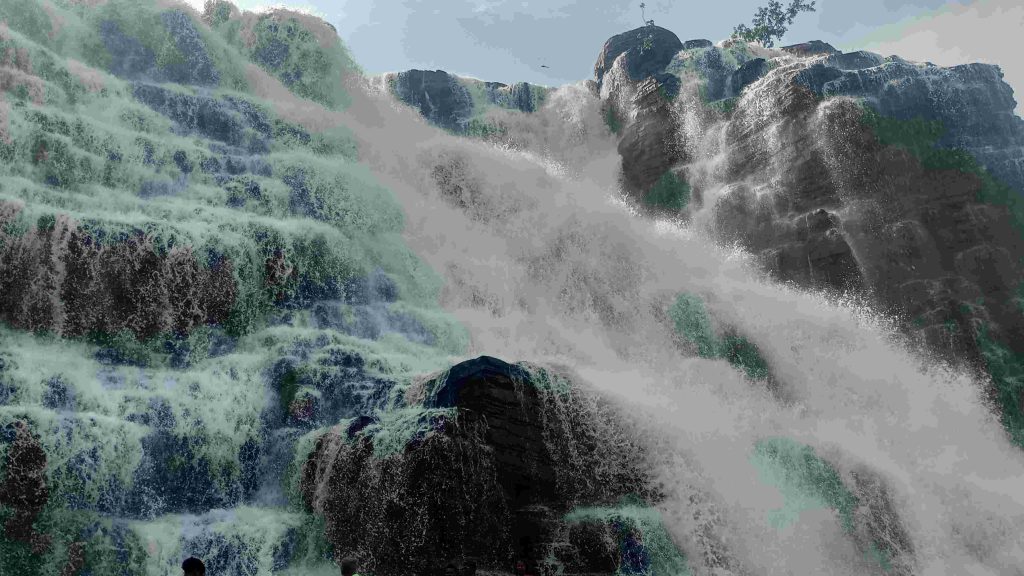

The TIrathgarh falls are located on the Kanger river – which gives its name to the national park. The Kanger, like the Indravati, eventually joins the Godavari, via Kolab and Sabari river systems. Unlike the Chitrakote falls, tourism flourishes at the midpoint of the falls. Most tourists exhibit their best bathroom behaviour in public. Apart from songs, one could witness fully lathered young men trying to emulate the Liril girl of the 80s – laaaaa, la la, laaa. The falls form an island in the middle where one can experience the splendour of a rainbow formed in the evening mist. A video that I shot had Meher walking around surrounded by a god-like-halo -thanks to optical mist manipulation. The Island had a set of stairs going closer to the base of the falls – and expectedly devoid of tourism. We enjoyed the serenity created by waterfalls and created a few of our own – while the missus had a small dip in one of the calmer pools of water.

What is interesting to note is trees with roots penetrated deep into the stone and also enveloping these boulders with nary a sign of soil around. So where do these trees pick up their water from? I am sure there are enough reservoirs below the stones sequestering water that will be useful during for these trees during the non rainy days. Or is it, as my friend Manohar Khake would like us to believe, that the leaf stomata directly capture the moisture for photosynthesis. Like leaves, we spent some time soaking in the moisture, leaving only as the sun started setting in the valley.

The drive back was through the same forest roads. By the way, this road connects Jagdalpur to Hyderabad, passing enroute through the Naxalite hotbeds of Sukma and Bijapur. Just 10 km from Tirathgarh is Darbha, the place where senior Congress leadership of Chhattisgarh was brought down by the Naxals in an ambush in 2013. Nowadays the state police have been supplemented by the Indian army which has set up a camp in Bastar. Naxalism has been a mixed bag for the locals, who are often caught in the crossfire between the state and the Naxal forces. Looking at the glass half full, Naxalism has helped retain Bastar’s forest cover. In India it is rare to find forests remaining in the plains –Bastar is an exception, though off late agriculture has started making inroads into the forests. One still sees quite a few trees standing in the middle of paddy fields. Wildlife is usually a menace to the buffer zone farmer, but thanks to the gun toting Naxals – most Bastar wildlife has been converted to lunches and dinners.

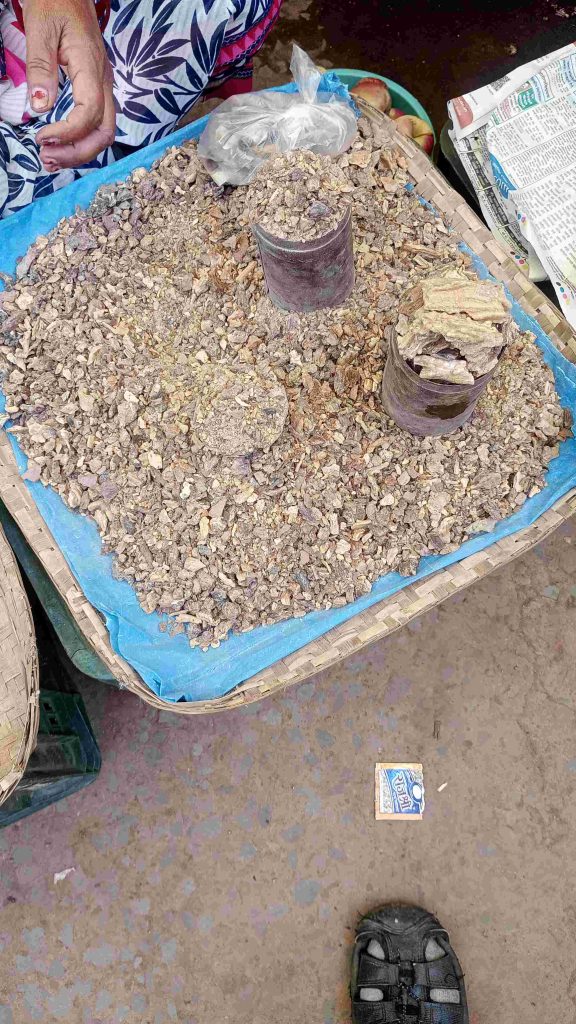

We reached Jagdalpur late evening, stopping enroute at a village haat, where we wanted to procure the local usna rice. We couldn’t get that, but ended up buying dried mahua flowers, which taste a bit like raisins. We were advised by the seller about the process of converting the flower to alcohol – you need to boil the flowers for a while to get the fermentation started. Am looking for non alcoholic use of the flowers. Past experience has made me wary – for I have experienced this flower power as a laxative.

The next day was a walking tour of Jagdalpur. We had breakfast at Atithi restaurant, located in the Zilla Panchayat campus on the new bus stand road. It is under the management of the same team that runs Hotel Atithi – which we had first tried to book, but were unsuccessful as the phone was not reachable. The restaurant manager shared the hotel number with us – but we tried again, and the call did not get picked up. Looks like Athithi does not want too many guests. The restaurant was a standing only one – and quite a few customers only came to pick up parcels. Thankfully, Swiggy and Zomato do not operate in Jagdalpur – so customers have to locomote. The manager was super friendly, the idli, wada and dosa were decent – but the kitchen hygiene was a bit suspect, with Ganesh-wahans roaming around. The tiles on the wall near the exhaust fan were broken – and mini oil waterfalls marked some of the tiles. Thin SS sheets to cover commercial kitchen walls can survive the high temperature and oil fumes. Tiles with thin SS covers may be the next big kitchen product idea!

We walked 2 km to visit the local Ma Danteshwari temple. The original is in Dantewada, which is one of the 15 shaktipeeths. The name comes from the legend that the Devi’s tooth fell here in some celestial battle. The rulers of Bastar shifted capitals from Dantewada to Jagdalpur and ended up building a temple here, to make it easier for the rulers to worship Ma Danteswari. The temple is part of the 27 acre grounds of the Bastar palace. The palace is more like a well maintained bungalow. Tourism is only allowed in a hall on the ground floor which contains photographs of the Chandrabhagas, the ruling dynasty. The first photo was take way back to 1910, which shows the seven year old king seated next to the British resident. This king died young in 1936. The current king was crowned in 1996.

We walked the 2 km back and bought fruits and veggies. Materialism got the better of us, as we ended up buying a brass tutari or bullhorn. The justification was that it will give us some good lung exercise. Missus and Meher attended the sermon at the local gurdwara followed by langar. Yours truly was shooed off because of dress code violation. After lunch, we headed back for a post prandial siesta.

Meher’s MSSRF colleague, Meera, was flying in from the MSSRF Chennai office via Hyderabad and Jagdalpur. Meher requested for a lift back to Jeypore – and she agreed. We reached Jagdalpur airport – which was only 2 km away from the hotel. Small airports feel so welcoming. In the space of 10 min, 2 Indigo flights landed – both Bombardier Turboprops. The first one was a CRPF special flight from Delhi, which makes two trips a week. The Hyderabad flight landed a few minutes after the Delhi one – but deboarding was allowed only after the Delhi flight taxied off for its return trip. The drive back to Jeypore was through lush green rice fields. We passed the NMDC Steel plant enroute; not too far from Jeypore. Road quality dipped as soon as you entered Odisha. We stopped for chai just before Jeypore, gifting a few bananas to the tea vendor and her school going kids who were playing around in the home cum shop.

Meera started her career with MS Swaminathan Research Foundation in Chennai and spent 1.5 years there. Ironically, the vegetarian Iyengar Meera went on to work with the Tamil Nadu government, on projects with the fishing community. One of her achievements was to popularise the use of ice to increase the proportion of fresh fish in the selling basket of the community. Drying is the best way to preserve fish, but dry fish doesn’t fetch good financial returns. Most of the dry fish market is is B2B and is dominated by menfolk. Traditionally women have been retailing fresh fish by getting the fresh catch from the village to the market. The richer women folk don’t participate in the retail trade; they are typically married into families which own and operate motorised boats. Nowadays, the retail trade is changing with fishing boats docking directly in harbours near the main markets. Also the bigger better fish are being sent across for export or metro markets, leaving the women folk with lower grade fish and lower returns.

Meera helped with a government scheme which provided free aluminium containers with a sieve at the bottom to collect the melted ice water. The implementation department, in its wisdom, decided to delete the sieve, resulting in a lot of rotten fish, by the time the iced containers reached the market. Most fisherfolk soon repurposed these containers to rice storage.

We reached the MS Swaminathan Research Foundation’s Jeypore campus by sundown. The MSSRF regional centre has a 12 acre campus. The land was donated by the government of Odisha. The main building is named after Biju Patnaik, Odisha’s first CM. The trainee hostel, funded by Mitsubishi, is next to the main block has to 10 rooms and two dormitories. MSS was the head of ICAR in its formative years. He was instrumental in introducing high yield green which help us become self sufficient in food grains. In the seventies we had to actually buy wheat from countries like USA to feed our population.(The 1972 wheat donation came coupled with an unintended gift – the invasive grass species popularly known as Congress grass). The campus is only 1.5 km from the airport and 2 km from the railway station, both of which are 4 km from the main town.

Agriculture remains the forte of MSSRF. During our stay at Jeypore, we interacted with the team that was working on creating community seed banks. High yield seeds sold by Odisha Seed Corporation can be used for up to 3 years after which the genetic math weakens; the fourth generation yield drops to very low levels. Hybrid seeds provide yields, which are better – 10 to 15% more than the high yield varieties. But the hybrid seed is sterile and cannot be used for subsequent crops. Farmers have done the math and prefer hybrids over the high yields. The hybrid seed market is dominated by the private sector, more so by MNC’s like Monsanto.

We met with two team members of Norway based Fridtjof Nansen Institute – www.fni.no. Miss Vasquez is a Columbian who works there. She was here to participate in the community seed project. We discussed the similarity between Columbia and Bastar. The key differences are the role of crops like cocaine etc in the forest ecosystem there. Thankfully, Bastar doesn’t face the same problem, probably the advantage of a having a militia governed by communist ideology.

The MSSRF kitchen team was at its best during the stay – thanks to a VIP contingent that had dropped in from Chennai HO. Plus the Norwegian team. I saw repeated violations of my non-lactic diet as I succumbed to the temptations of kheer and paneer. The absence of significant milk in the diet has changed my bacterial gut culture. The lactose digesting bacteria have disappeared – and most milk passes undigested down the GI tract – resulting in mild diarrhoea whenever milk is consumed beyond a low threshold. The digestive ill health did not result in behaviour change –the next meal featured ras malai. Yours truly had the rasgulla, while the missus had the malai.

The next day, Meher had arranged for a talk of Yours Truly in a school adopted by MSSRF. The school was at a village called Lima, about 30 km from Jeypore. There are no Panchayat schools nearby. The aim is to make Lima a child friendly village. I chatted up with Kalu ji, the owner of the company that rents cabs to MSSRF. Kalu ji is from Behrampur. Kalu’s son, Suraj, works as a data entry operator at MSSRF, in the healthcare team. Kalu’s wife runs a kirana store at their house. They have a daughter, who is a government school teacher – and also married to another government school teacher.

Kalu started his career as a driver with the Odisha Horticultural department. A defining characteristic of entrepreneurs is under-average boss management skills . Kalu left government service after a fight with his boss, and took a Rs 2 lakh loan from a money lender to buy his first car, an ambassador. The interest rate for the loan – only 10% per month. The initial years were tough – four accidents happened in the first two years, setting business back by quite a bit. Today Kalu ji has a fleet of 8 cars – Swift Dzires, Ertigas and Boleros. He likes the Innova, but Odisha clients don’t have budgets for bigger vehicles. Apart from MSSRF, his other big client is Food Corporation of India, which pays better and faster than MSSRF. FCI is a powerful agency in Odisha; when it comes to paddy, farmers have no choice but to sell to the government.

BILT started a paper mill in Jeypore in 1984, but had not capitalised it well. They sold the unit to Mother Earth resources – but they too were not successful. The unit has been shut since 2019 – there was an attempt to restart it in 2024 – but that did not last long – thanks to troubles with the 9 unions that created chaos inside the plant. The lasting legacy of the mill has been a change in local cropping patterns. Eucalyptus is the new cash crop in town now. Wood quality and water intensiveness doesn’t matter so much – its like hybrid chicken – grow fast, harvest fast. There are enough papers mills in neighbouring Andhra and the adjacent district of Raygada to create demand for wood chips.

We reached the Lima school at around 11:15 hours and chatted up with Sushant Dash, the principal of the School. There are three divisions of 50 students each in the Odia medium school. The government has sanctioned two teachers each for arts and science, one for Sanskrit and one for Hindi. It is difficult to get teachers for science and maths. So Sushant ji used to take science and maths classes. A science teacher has joined recently. After the rule for no failure was abolished, grade inflation has increased. To their credit, teachers offer special coaching for students of 10th standard. 90% of the students from the school study up to standard 12. About 60% do graduation, mostly in arts. The kids in the school come after being filtered from the central schools and model schools. Many students from the school have become teachers. A few have joined defence forces and some are working for companies. One student has joined RBI in Pune and is doing well.

Apart from his academic duties, Sushant ji also manages lodging and boarding for his wards. Homesick students at times jump over the boundary wall to go home. To keep these unscheduled leaves in check, student attendance is taken even at dinner time. The school is a residential one, with the hostel accommodating 150 boys and 100 girls. Rs 1000 per student is sanctioned by the government for the meals. Government gives the rice at 1 rupee per kg, which is transported at a cost of Rs. 3 per kg from a depot near the paper mill, about 12 km away. Cooking is done on chulha, but when firewood is not available, as in the rainy season, they have seven cylinders for cooking.

We had a one hour session with students on career planning. This was followed by a 15 minute interaction with teachers. I could not locate a Bisleri bottle on campus, which disrupted my plans of demonstrating a pressure activity. In a way, absence of plastic is a sign of a sustainable school. Only one of the 4 teacher groups anticipated the activity outcome; tragically this group did not include the current science teacher, but it did include the teacher who was incharge of the plumbing sklls lab. (Having vocational courses in the school is a fantastic idea.) We ended with a Q and A. Groups of teachers came up with one question each. Their questions and my responses below:

How to motivate students who are not interested? Make groups of students; the relatively better student guides the relatively weaker students.

Day scholars do not come to school, what should be done? Gijubhai Badheka has written a books – Divaswapna, which is available online. This is a story of a teacher in pre-independence Gujarat – and talks of a few tricks to increase the interest level of students.

Government regulations are made without bothering about constraints of syllabus and teacher time. What should we do? Managing documentation is a survival skill for a government teacher. So I assumed that the question is a rhetorical one.

Some children have not gone to primary school but in 5th standard they cannot even write their names. What should we do? Make groups of 5, with one fast learner in charge of the 4 slow learners.

After the teacher interaction, we had a look around the school. Saw the library, science lab and computer lab. There was also smart board in the auditorium. There was no internet access as the BSNL line had gone kaput two weeks earlier. Next time should have a dekko of the plumbing lab. Meher wanted ideas on involving the Lima kids in improving village level hygiene. I suggested starting with the school itself – and having a leader board for ‘green’ actions. A student has a target to do a a green/clean activity every day. In any kind of leader board, streaks are important. Documentation is done and shared publically in the school. So activity streaks are visible to all in the school.

We took the advice of the Sanskrit teacher and stopped 4 kilometres down the road for a traditional Odia lunch, in the premises of a Jagannath temple. Lunch is served from 12:30 to 15:30 hours. Preparation is done in small batches to minimise wastage, so a few customers have to wait for her to deliver fresh food. Lunch was rice and potato in multiple disguises – a gravy format, a pakoda format and as an ingredient of parbal sabzi.

We reached the MSSRF campus at 15:30 hours. After the customary siesta, we headed out to check a cashew processing factory in the neighbourhood. Started by purchasing one kg of cashew – its easier to request a factory visit after you make a purchase. This is philosophy that I have learnt from my friend, Bhushan Apte, who always tips hotel staff at the start of the stay – and ends up getting good service most of the the time. Whole cashew was priced at Rs. 850 a kg – and Rs. 800 for cashew halves / quarters. There was even cashew chura for sale – which retailed at rupees 300 per kg, but it contained a lot of skin, which gives a bitter taste. This gets sold to restaurants, which use it in cashew gravy, with other spices drowning out the skin bitterness.

The factory relies mostly on African cashew, as local cashew availability is only for a couple of months a year. One wonders why the Africa growers have not been able to invest in processing facilities. I remember Saikat Chaudhary, my IIM Calcutta batchmate, talking about how Africa has not been able to make inroads into cashew processing, in spite of being the largest producer of cashew. There were attempts made to start units in Africa – labour was taken from India for the factory. The challenge was the absence of a market for ‘brokens’. A 20% breakage is the norm in cashew processing. The Indian market absorbs brokens in all sizes, making the business profitable.

The shell is broken by a hand operated splitter. The shell is sold to the companies that process it to extract solvent used by the paint industry. The nut is then put into dryers to remove moisture. The thin skin is removed after drying. The nuts are then sorted on size and colour by a camera equipped machine. The yellow nuts fetch a lower price than the white ones – though there is no difference in taste. Second stage sorting is done manually (womanly would be more appropriate). The women clip off any skin that is adhering to the nut and remove brokens that the camera was not able to detect.

The Chennai team and the Norwegians left in the morning to continue their surveys in other districts. The missus and yours truly chatted with Asith, who looks after the health care project which is partly funded by the Gates/French foundation. The healthcare challenge is temporary migration – especially to Andhra Pradesh during rice planting season. Another challenge is the lack of roads which delays patient referrals to medical facilities. MSSRF has appointed volunteers in villages for update them about health emergencies.

Plan is to have will village level monitoring to do proactive work on TB prevention. Sanitation is an issue with drinking water contamination leading to outbreaks of cholera. MSSRF needs to incorporate sanitation goals in the project (maternal and child health are current focus areas). Solid waste management, especially plastic is the key. Case in point is the road leading to MSSRF Jeypore campus. It is in bad shape, as roadside drains are cluttered with plastic. Garbage dumping grounds exist across the railway line, but garbage collection is sporadic.

At policy level, standardising packaging and discouraging multi-layer packaging should help recycling. Mandating food grade PP will also help the recycling cause – as it will generate significant income for the waste collection workforce. The FMCG industry needs to participate in recycling and there should be measures in FMCG like CAFE, used for the auto industry. Aggressive targets should be assigned to the sector to reduce packaging use. A good model to follow is cookies distribution in pan shops. The cookies are sold in jars and are retailed without packaging. You will rarely find these jars in dumping grounds. They tend to get repurposed for household storage – and when its utility reduces even for that purpose, it is more likely to get recycled. My observation of urban litter tells me that in FMCG, pan masala would be a good place to start.

Moving on to other healthcare challenges, one more is micronutrients. 60% of women have low levels of haemoglobin: 6-7 gm/100 ml of Hb is common as against the norm of 12. Cooking in aluminium vessels needs to be replaced by cooking in iron vessels; the use of jaggery instead of sugar can also increase the iron uptake. Another challenge in micronutrients deficiency is malnutrition. Rice is a major provider of calories to the Odiya people. With high yield rice, the genes have been re-engineered to amplify the carbs. The incentive for agriculture is driven more by economics than consumer health. So traditional grains, which had a good mix of micro nutrients, are losing their share of the Odia plate. The farming community has to switch back to traditional varieties for self consumption!

We started a walk to the Jeypore bus stand. 500 m into the walk there was a sudden change in weather, as it went from sunny to thunderstorms. Unlike Pune, when it rains in Jeypore, it pours. We spent an hour in the tin shed parking of a building and watched water levels rise. We managed to catch a share auto as soon as the rain intensity reduced. Lunch was an Oriya meal at hotel Jhill, which gets its name from a lake next door, with plenty of white lotus in bloom. By the time lunch got over, the sky was clear again. We did some fruit and veggies shopping. We visited Maharaja sweets to once again torment the gut bacteria by sampling the local rasgulla. We ended up eating a higher density one – bought some for Meher and took an auto back to MSSRF.

Around 1830 hours, we left for Meher’s house for dinner. Mamta and Meera accompanied us. Meher had given us the contact number of an auto driver who knew his place – and agreed to ferry us to and from the venue. Meher stays in a place that I have always dreamt of as an ideal house – he rents a single room, about 2.5 km from the MSSRF campus. There is an attached toilet, and also a big attached terrace! It was an ideal dinner, with collective cooking. Yours truly and the missus conjured a karela sabji. Meher made bajra khichdi and a root vegetable that we had picked up in Jagdalpur. The evening was devoted to music with Meher’s Saregama device competing with Meera’s YouTubing of Tamil, Bangla and Odia songs. Meher and Meera are talking encyclopaedias on the Hindi music industry. It was nice to hear the banter on how Lata refused a retake on an OP Nayyar song – and was subsequently blacklisted by him.

We woke up the next day to find that we would have to do a major rejigging of our travel plans. The earlier plan had been to travel by train for an overnight stay in Araku valley. Train ticket booking had been done accordingly. But boulder falls ahead of Jagdalpur had led to the cancellation of services for 3 days. A cab to Araku was available, which would cost us Rs. 3200. Online search indicated an OSRTC service to Araku at 13:30 hrs. One more option was to take a direct bus to Vizag and continue our tourism there. As I was mulling over these permutations, I got a message from Manoj Tarale, a COEP friend, inviting us to visit Hindustan Aeronautics Ltd’s Koraput engine plant, where he was putting up a chilling plant. We immediately decided to shun all the past permutations and go ahead with the HAL option.

Caught an OSRTC airconditioned bus to Koraput, after a half an hour wait. The ticket for the 20 km journey cost about the same as what PMPML bus charges me from home to Pune railway station – 5 km away. The road from Jeypore to Koraput is fantabulous – you are continuously climbing through green non-eucalyptus forest and small paddy fields. Every time you look out of the window, you see picture postcard scenery. We should plan a cycling trip here in the near future. Getting down at Koraput bus stand, we located an eatery in the premises – Hotel Kadambari. We walked in for a cup of tea, but the restaurant did only meals. It was only 12:30 hours and we were not really hungry. We requested the owner to keep our bags – promising to return back for lunch in an hour. Thankfully the hotel proprietor agreed – and we enjoyed a 3 km trek around town.

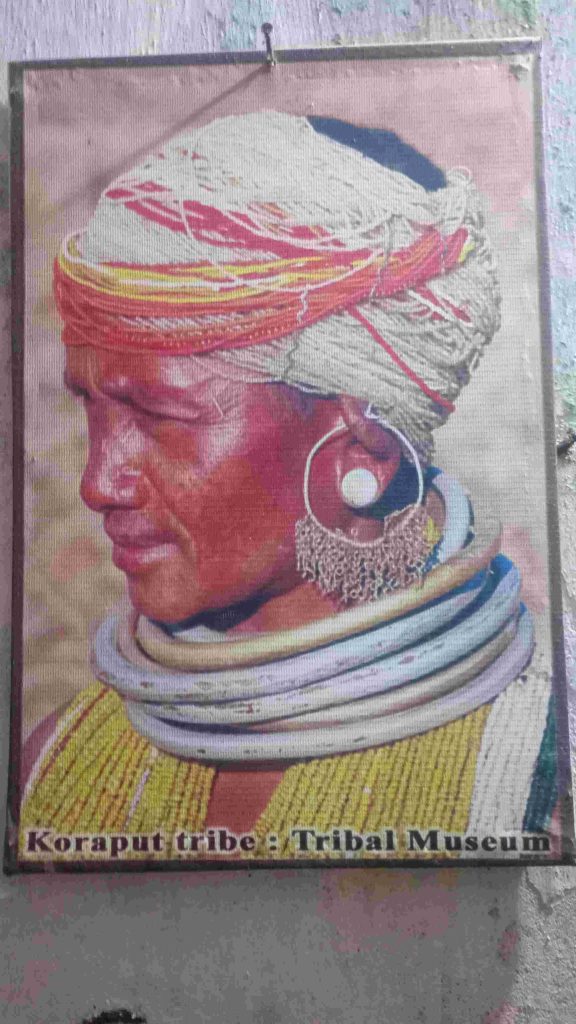

Meher had recommended that we visit the tribal museum, about a kilometre away from the stand. The premises occupied by the museum were initially used by the tea districts labour association, which started functioning in 1923. From 1923-56 the association annually recruited about three thousand people from Koraput to work as labourers in the tea gardens of Assam. The association was shut down in 1957 and its buildings were then handed over the Dandakaranya project which was set up in 1958 to resettle East Pakistani refugees in parts of Koraput. After the Dandakaranya project was wound up, the compound has been occupied by the Koraput district administration. Happy to see quite a few tribals visiting along with us. And even happier to note that the entry ticket to the museum was a meagre Rs. 5.

The museum had the usual tribal artefacts, but what was different was an entire section on rice. There were probably 25 rice varieties on display, which honestly did not make for an appealing exhibit. Food is a multi sensory experience, with taste, touch and feel mattering more than sight and sound. What if like a kirana shop, we could touch the grain, feel the aroma of the individual rice varieties, choose one and cook a bit – all for a larger price, of course. Google Lens is a good note taker – and I have collated some of the content of the interesting posters:

Humans domesticated rice about 10,000 years ago, as the Pundits say, from jungle grass whose wild relatives still survive in Koraput region. The present Eastern Ghats were a part of the ancient Gondwana land-mass. Before the Dravidians entered this region the ‘Nishad’ civilisation was prevalent here. The ‘Nishadas’ were proficient cultivators. The climate of this region was favourable mainly for the cultivation of grass, like paddy. They had chosen paddy from nature and introduced in their cultivation. Hence, the first paddy cultivation was adapted in Koraput region where the ‘Nishada’ Civilisation had developed. Later the Nishadas are called as “Hill Tribes.

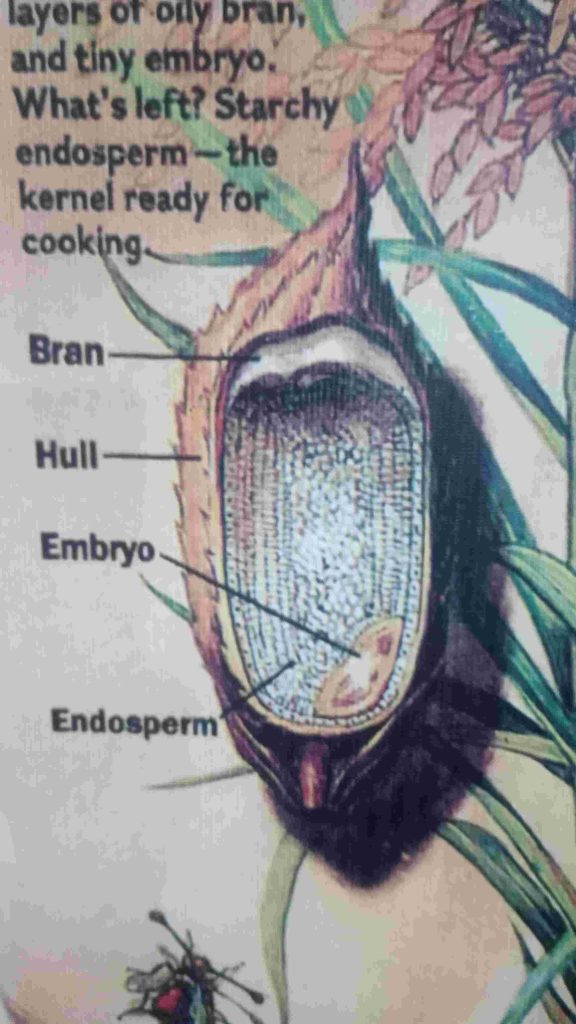

Rice is a grain belonging to the grass family. It is related to other grass plants such as wheat, oats and barley which produce grain for food and are known as cereals. Stripped during milling, a grain of rice loses its tough hull, layers of oily bran, and tiny embryo. What’s left? Starchy endosperm-the kernel. Rice refers to two species (Oryza sativa and Oryza glaberrima) of grass, native to tropical and subtropical south eastern Asia and to Africa, which together provide more than one-fifth of the calories consumed by humans. The plant, which needs both warmth and moisture to grow, measures 2-6 feet tall and has long, flat, pointy leaves and stalk-bearing flowers which produce the grain known as rice. Rice is rich in genetic diversity, with thousands of varieties grown throughout the world.

Throughout history rice has been one of man’s most important foods. Today, this unique grain helps sustain two-thirds of the world’s population. About four-fifths of the world’s rice is produced by small-scale farmers and is consumed locally. Rice has been grown for more than 6000 years in South Asia. More than 40% of the world’s population depends on rice as the major source of calories and 155 million ha of rice, of which 79 million ha is irrigated, are harvested annually with a production of about 596 million metric tons. More than 90% of this is produced and consumed in Asia. As the primary staple food, it provides more than 50% of total calorie intake in many Asian countries. The intensive irrigated rice systems belong to the most important food production systems on the earth.

Since the 1930s, researchers have generally agreed that rice originated in a single wild species – in the humid zones of the supercontinent Pangwa, before it branched out and drifted apart. This can also explain the parallel evolutionary pattern of rice in Africa and Asia respectively. It also reconciles the presence of closely related wild species having the same genome in Australia and South America. Thus, the antiquity of the genes date back to the Cretaceous period of more than 130 million years ago.

The gathering-and-selection process was more imperative for peoples who lived in areas where seasonal variations in temperature and rainfall were more marked. The earlier maturing rices, which also tend to be drought escaping, would have been selected to suit the increasingly arid weather of the belt of primary diversity during the Neanderthal period. By contrast, the more primitive rices of longer maturation, and those, thus, more adapted to vegetative propagation, would have survived better in the humid regions to the south. In some areas of tropical Asia, such as Jeypore, Batticoloa in Sri Lanka, and the forested areas of north Thailand, the gathering of free-shattering grains from wild rice can still be witnessed today.

On our return journey we peeped into the freshly painted Jagannath Temple. It was gleaming in white and looking quite modern. India’s penchant for afternoon siestas has its origins in Lord Jagannath. Our friend always has one – and temple doors are locked as the lord slumbers after his afternoon bhoj. The bhoj is so important that most Jaganath temples serve lunch as Prasad. Unlike the gurudwara, the dakshina of Rs. 70 was involuntary. We could not eat the Prasad, as we had kept our promises and luggage at Hotel Kadambari. Nevertheless, we had a darshan of the kitchen and watched the assembly line put together thalis of the usual staples: rice, dal and a few veggies. There was a huge hall where you can sit at random places and eat. To my surprise, the dining area was spick and span, seemingly without too many cleaning staff.

The temple was also a museum of sorts- Jagannath was dressed in about 20 avatars. And next to the dining area you had replicas of deities from across India – ranging from the sleeping God of Sriirangapatna to Vaishno Devi of Jammu. We went down a flight of steps to get to the bus stand. Our lunch Prasad was at Hotel Kadambari, with yours truly having a veg thali and the missus making do with curd rice. As in Hotel Jhilli in Jeypore, vegetarians were a minority in this restaurant too. What makes fish, poultry and meat popular in the eastern ghats? Probably the hunter gatherer roots are stronger here. Probably, the local plant based diets don’t deliver on proteins. Like everything else in Odisha, even non veg food is value for money.

Lunch done, we boarded a bus to Similiguda, 20 km away. The bus driver had just had his lunch and so wouldn’t start without doing justice to his siesta, so we also enjoyed one for the next 30 minutes. By then the bus had filled up with enough locals to justify the trip for the bus proprietor. Google maps informed us of the presence of a lake formed in the valley that spans almost 3 states. We crossed this lake twice in our 20 km journey. I wonder if this is result of some human engineering or was it always like this. (Ans: It was always like this.) We reached Similiguda at 15:30 hours and based on Manoj’s reco, checked into hotel Lemon Castle, which had fares in the Lemon Tree Territory. Manoj was also staying at the same hotel.

Manoj was at the HAL factory, so we decided to do some opportunistic tourism and walked down a kilometre to the HAL museum. We were lucky; the museum had just opened after a monsoon break of 2 months. Getting into the museum was like taking a tour of the HAL factory. There is a MIG 21 which you can touch and feel. They didn’t let us inside the cockpit, but you could peek into the fuselage – and hunt for the rear wheel storage bays. (PS: I couldn’t find it.) The nose wheel assembly most likely pivots towards the nose.

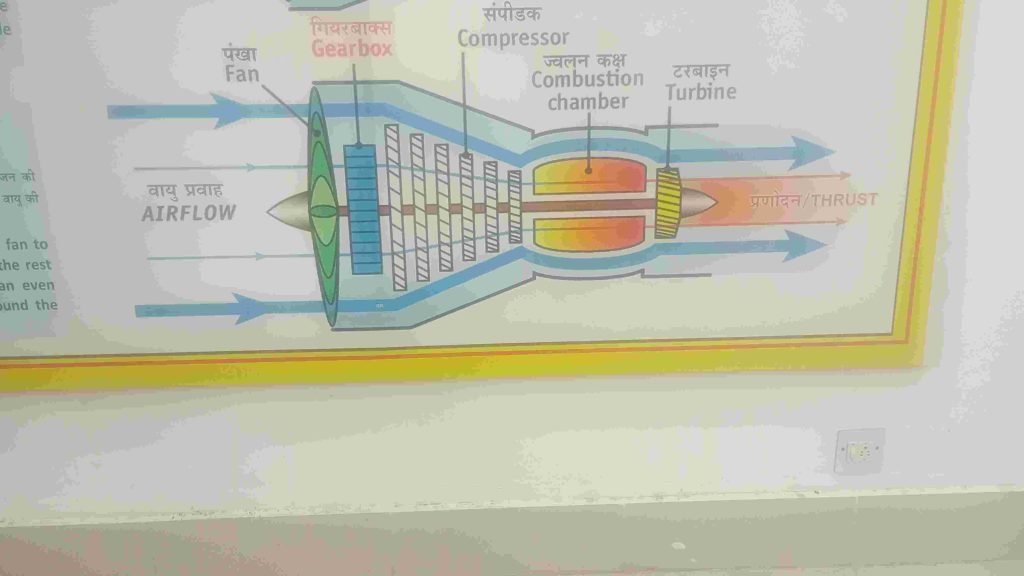

There is a small enclosure for the pilot in the airframe, which is essentially a tube to hold the huge engine. Air is drawn into the tube from the periphery of the nose cone and goes directly into a fan. The fan rotates at a much lower RPM than the main Jet engine. The first two blades rotate with the fan and build pressure. There is a reduction gear box that takes power from the in turbine shaft and drives the fan. The next three compressor blades are directly mounted on the turbine shaft. These are housed in a conical cowling, with the blades on subsequent rings becoming smaller to increase air pressure. The compressed air is fed into a combustion chamber, where fuel is burnt in 12 burners.

The most fun part of the museum is the engine exhibit, which is kept in the backyard. No tourists were visiting the engine area. I tried rotating the fan and was thrilled to see it moving. The bearing did a good job – the fan and part of the blade assembly continued to rotate for more than half a minute. A jet engine is all about Newton’s third law – action is equal to reaction. The thrust of the plane is determined by the momentum of the exhaust gases. There is a diffuser at the end, which probably serves to convert some of the pressure into velocity. Exhaust gases drive the turbine, which powers the compressor and also the electrical systems of the aircraft. After the turbine, the cowling cross section reduces, as the gases flow over small internal cone to create the jet

The museum sits on a small hill. As kids played on the strings and slides, we admired a rainbow that had emerged in the evening Sun. We were entertained by the murmurations of a flock of swallows – (thanks to Ajay Jandial for identifying the birds.) The birds had made nests under the museum window ledges.

We walked back to town and did some veggie shopping. Samosas were quite popular in town. At 997 m altitude, Similiguda has ideal weather for samosa snacking. (Just to benchmark Pune is at 560 m, Araku at 910m and Bangalore at 960 m). The samosas had groundnut and potato and were served with two chutneys. I had tears in my eyes, not from the spice. Only in an Odisha samosa, can you realise the power of 5 rupees in 2025!

Ganesh puja has become popular in Odisha and every pandal had a different Ganesh ji aesthetic. One had a veena playing God, another had an angelic Ganesh with small wings. We sampled the prasad in two pandals before heading out for dinner with Manoj at Imperial Hotel, the hippest place in town. We over did the carbs with missi roti and laccha paratha. The high point was a radish salad, made from a fresh bunch of radish that we had purchased at the local Bazaar. The leaves and the radish were actually sweet. It must have to do something with the pollutant free water that irrigates the fields near Similiguda. The last deed of the day was a visit to a local Vishal Mart to purchase a track pant for the HAL factory visit. As usual I was in shorts and factory rules don’t allow shorts folks into the campus.

We checked out of the hotel and caught an auto to the gate of the HAL engine division. We had to wait 15 minutes for an escort. Every visitor has to be accompanied by an HAL employee . Visitors have to deposit their phone at the security case – only use of non smartphones, without cameras, is allowed in the factory. We also deposited our backpacks, as Manoj had warned us about the long walks inside the campus between sheds.

Quite a few of us don’t know of Walchand Hirachand’s connection with Hindustan Aeronautics. In 1939, a chance acquaintance with an American aircraft company entrepreneur inspired Walchand Hirachand to start an aircraft factory in India. Hindustan Aircraft was started in Bangalore in the Mysore State with the active support of its Diwan, Mirza Ismail in December 1940, the Kingdom of Mysore was a partner in this venture. Walchand Hirachand started life as a contractor. His first big project was the construction of the railway line between Bombay and Poona in the early twentieth century. He then went on to found an industrial complex at Sangli, which still manufactures sugar machinery. Those of us who grew up in a pre-Maruti Suzuki era will remember the rugged Premier Padmini, based on Fiat models. That was also WH’s handiwork.

During the museum visit, we had come across an exhibit about turbine blade manufacturing. We could manage a visit to this facility. The entire work area is ventilated by air handling units to reduce chances of dust and moisture contamination. The blades are made of nickel alloy, which is till date sourced from Russia. The sand cast is made using a green wax. Solvent is used to remove the wax core after sanding has been done. The sand is critical as it has to withstand a temperature of 1600 degree centigrade. It is made by mixing multiple ingredients and making slurry, which is sprayed on to the wax framework. This is heated for 15 hours in an oven to melt the wax and remove the moisture.

The nickel alloy pouring happens under vacuum to prevent oxidation. Graphite electrodes are used to supply the DC current to heat the alloy. The mould is preheated to red hot before the pouring, to prevent premature cooling of the nickel. There is a reservoir of molten aluminium on which the mould sits. The crystalline structure is achieved by using a Nickel Tungsten seed crystal at the bottom of the mould. The mould is dipped gradually into the molten metal for the single crystal block to form. The AIuminum bath serves to control the rate of cooling; too fast a cooling rate can result in multiple grains. Every blade is x-rayed to confirm not only the single grain structure, but also to check the orientation of the grain. Grain orientation tolerance is +/- 5 degrees with vertical. Here is a note on the process detailed in the museum exhibit:

Single Crystal Blade Casting is manufactured by keeping molten metal in a Ceramic Mould in molten stage and allowing it to solidify at a pre-determined cooling rate. The mould is kept at a high temperature (1500-1600°C), and solidification is allowed to start, usually at the bottom of the mould where a Seed Single Crystal (Ni-W Button) is placed. During solidification a single grain / crystal having crystallographic orientation grows from the seed crystal.

In a hollow thin walled turbine blade casting, internal cooling passages are formed by a sintered ceramic core. A mix of fused alumina mass of different grain sizes in molten wax base is injected under high pressure. The injected green cores are then sintered in an alumina bed at 1350°C for 15 hours. The sintered cores are then removed and impregnated in an organic solvent. These sintered cores are then taken for wax pattern making.

There are two divisions in the factory. The new division makes engines for Sukhoi jets. With MIGs on their way to decommissioning, the Sukhoi division is now where the action is. The original engine factory was built in 1964 and age has started to show. Quite a few buildings look run down. In contrast, the Sukhoi setup has new buildings and more machines centres than lathes. We visited one of the machine shops and spent time with a senior manager, who had worked on all the stages of the Light Combat Aircraft program. He was a patient teacher. Here is gyan we got from him:

- Titanium can work on operating temperatures up to 600 degree. Nickel can operate at 1200 degree centigrade. The catch – nickel comes with a weight penalty ; its density is 3 times that of titanium.

- To manage weight, the combustion section of the engine has a titanium casing with a kind of nickel lining. Nickel sheets are corrugated to create air passages which serve dual purpose: insulation of the titanium casing – and air pathways required for combustion in the after burners.

- The Sukhoi engine is a turbofan jet. The compression happens in nine stages, compressing air to 23 times ambient. At a plane’s cruising altitude, which can be as much as 50,000 ft, ambient pressure can be as low as 0.1 bar.

- The first stage of compression is a fan, which rotates counter to the turbine blade, with an RPM that is much lower. This means lower turbulence and higher fuel efficiency.

- The next two stages are using conventional blades – about 50% of the compressed air is directed to the periphery of the engine – and from then on plays no role in combustion. This air is colder – and denser – and therefore provides relatively high thrust when pushed out. The higher the proportion of cold air, the better the engine efficiency.

- Bernouli’s theorem is applied when hot gases are pushed through a double cone. One can do away with the expanding diffuser if one is flying at speeds less than one Mac h. For supersonic speeds, you have to have a diffuser to convert velocity to pressure. (Check this.)

- The afterburner is provided to increase thrust. Afterburners are used sparingly, typically during combat manoeuvres. Use is restricted to about one hour per thousand flying hours. After burners do obstruct the exhaust gas flow, lowering efficiency, but are an operational constraint.

We finished the HAL tour with lunch at the Sukhoi canteen, where expectedly most people were enjoying a subsidized non veg lunch. We stuck to our usual veg thalis, which were priced at Rs. 35. Manoj walked us back to the main security gate. We trekked 1 km with backpacks to the highway. Courtesy Manoj, we had been booked into an APSRTC bus for Vizag .

About half the bus journey was through the ghats – and was a feast for the eyes. I chatted up with my neighbour about life in the hills. For the Koraput tribals, even the Gods are locals. There is a puja almost every month. August is for the rice planting God. Rice and Maandya (nachani in Marathi) are traditionally grown staples. Nowadays, maize cultivation has picked up as a cash crop. Maize is grown mostly on hills slopes and rice in the valley. Maize is supplied to starch manufacturing units. Thanks to the extensive water bodies, fish is also a part of the local diet. Desi poultry is preferred, even if it rivals goat meat in pricing. Locals own cattle, but cattle is used mostly as a source of gobar fertilizer. Like Yours Truly, locals don’t consume milk.